It’s time. Time for the final installment of my epistemological essays on the Münchhausen Trilemma. I’ve written about it on four prior occasions:

The Horror of Münchhausen's Trilemma (Oct 21, 2020)

Why Struggle Against the Trilemma (Oct 31, 2020)

The Münchhausen Trilemma presents a challenge to the justification of knowledge. It proposes that any attempt to justify knowledge will ultimately lead to one of three unsatisfactory options:

Circular Reasoning: The truth asserted involves a circularity of proofs.

Infinite Regress: The truth asserted rests on truths themselves in need of proof, and so on to infinity.

Arbitrary Assumption: The truth is based on an unsupported assumption.

In the essay Defending Against the Trilemma I argued that three laws of logic and two axioms of empiricism are irrefutable. They are:

The Law of Identity: Whatever is, is.

The Law of Non-Contradiction: Nothing can be and not be.

The Law of the Excluded Middle: Everything must either be or not be.

The Axiom of Existence: Existence exists.

The Axiom of Evidence: The evidence of the senses is not entirely unreliable evidence.

The first four are well-known, but the fifth is an axiom of my own formulation. As I explained in the essay,

The Axiom of Evidence is an axiom of my own formulation, although not my own creation. I first formulated the wording during a heated argument with Professors Scott Brewer and Robert Nozick at Harvard Law School. The question had arisen: How can we know that our senses are reliable? After all, straws seem to bend in water; the same shade of gray can change in apparent hue based on nearby colors; hallucinations can confound our vision; and so on. My response was that all of the evidence for the unreliability of our senses itself arose from the senses. A true skeptic of sensory evidence could not even argue that the senses were totally unreliable because he’d have no evidence with which to do so. And even if he did have such evidence, he’d have no way to use it to refute a proposition, because that refutation could not be reliably made absent the senses.

Of course, we still haven’t gotten very far. While it’s true that the proposition “the evidence of the senses is not entirely unreliable evidence” is irrefutable, the Axiom still leaves open the question of how much is reliable, and to what extent. That will be the topic of a future essay, where we will discuss the crossword puzzle theory of epistemology known as Foundherentism. Foundherentism, as we will see, is consistent with my theory of irrefutable axioms, and protected against the Trilemma.

In The Rarity of Noesis, I argued that noesis, the faculty of apprehension of truth, enables some people to see that these three laws and two axioms are not just irrefutable, but are true. They are the noetic principles, and that the fact that skeptics are skeptical of this is evidence merely that the skeptics lack noesis, not that their skepticism is warranted. As I put it, “If a color-blind man says he doesn’t see color, you can believe him. If a color-blind man says YOU don’t see color, you shouldn’t believe him.”

Today I want to explain the broad epistemological approach that I alluded to in my earlier essay: foundherentism. Foundherentism is a theory of epistemic justification that combines elements from the two other major theories, foundationalism and coherentism.

Foundationalism is the view that certain beliefs are justified independently of other beliefs. These are often called basic beliefs and are supposed to form a foundation upon which all other justified beliefs are built. In other words, there are certain self-evident truths or experiences that require no further justification. Foundationalism is divided into rational and empirical foundationalism.

In rational foundationalism, the laws of logic forms the basic beliefs. However, in the absence of a justification for empirical evidence, rational foundationalism leaves us “stuck inside our own heads,” unable to have justifiable beliefs about the real world.

In empirical foundationalism, sensory evidence forms the basic beliefs. However, individual instances of sensory evidence are always susceptible to challenge (as being hallucinations, illusions, or errors). This problem has tended to cause empirical foundationalism to either collapse back into rational foundationalism (which gets us nowhere) or into coherentism.

Coherentism rejects the idea of basic beliefs. It suggests that a belief is justified if it coheres (fits together) with a set of beliefs or propositions. The more coherent a set of beliefs is, the more justification it has. Coherence is generally associated with logical consistency, explanatory connections, and various other related features.

Foundherentism was primarily developed by philosopher Susan Haack in an attempt to merge these two theories and resolve some of their issues. Foundherentism proposes that all beliefs are justified by being part of a coherent system while also being tied to the experiential ground. Hence, it maintains a foundational aspect (experiences provide a kind of base) while also insisting on a coherence aspect (justification involves fitting into a network of beliefs). Hence, foundherentism attempts to strike a balance between the necessity of a grounding experience (foundationalism) and the requirement for our beliefs to make sense together (coherentism).

According to Haack, a belief is justified if and only if it is part of a system of beliefs that stands in the right kind of coherence relation (coherentism), and this system includes at least one belief that is reliably produced (foundationalism).

But what makes a belief “reliably produced”? Haack never answers this question. She tacitly assumes that empirical evidence is somewhat reliable, but does not explicitly assert the axiom of evidence. We shan’t make that mistake: It is the axiom of evidence which allows us to be justified in believing that empirical evidence that is coherent with all other available empirical evidence has been reliably produced.

According to my version of foundherentism, a belief is justified if and only if its part of a system of beliefs that stands in the right kind of coherence relation (coherentism), and this system is founded on all five of the noetic principles, including the axiom of evidence, the latter of which necessitates coherency!

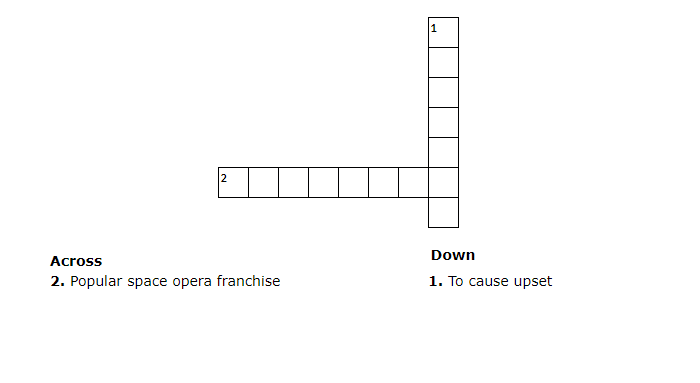

The easiest way to imagine this scheme of knowledge is to think of a crossword puzzle, which is the analogy Haack herself uses. For those of you who are under the age of 21, a crossword puzzle is a popular type of word game that used to be played by people who read something called the New York Times. Crossword puzzles used to come in many forms, but the traditional format had a grid of blank white squares where the words are placed. Here are the general rules for solving traditional crossword puzzles:

Objective: The goal of a crossword puzzle is to fill in all the white squares with letters, forming words or phrases, by solving the clues which lead to the answers.

Numbering: Every word in a crossword is normally numbered, and these numbers correspond to numbered clues. The clues are split into two categories: "across" (horizontal) and "down" (vertical). Words are entered based on these clues.

Clues: Each clue provided is a puzzle in itself. The clue might be a direct synonym, an indirect hint, or involve wordplay, depending on the type of crossword. The word entered must be in accordance with the clue.

One Letter per Square: Each white square must be filled in with one and only one letter.

Crossing of Words: Since some white squares appears at the intersection of two words, once in the “across” word and once in a “down” word, and the square must have one and only one letter, the correct answers to the clues will be words that share the same letter at the point at which the words cross.

In our foundherentist theory:

The crossword puzzle represents our belief system.

The rules of the crossword puzzle represent the noetic principles.

The answers to the crossword puzzle represents our beliefs.

Each clue represents a piece of empirical evidence collected by the senses.

A set of answers that completes the crossword puzzle without violating any of the rules is a justified belief system. The larger the crossword puzzle, the more justified the belief.

Here is a simple crossword puzzle that we will use to elaborate our theory:

The Empirical Foundationalist Crossword Puzzle

Here is what that crossword puzzle looks like to an empirical foundationalist who does not agree with the noetic principles but just relies on “empirical evidence”:

The empirical foundationalist does not see any need to concern himself with whether his two answers are coherent. If that sounds absurd, it’s not. Philosopher Nancy Cartwright’s book The Dappled World argues that’s exactly how science has come to understand the world, as a series of unconnected beliefs that are not coherent with each other. The most famous example of this is quantum theory and relativity theory, both of which empirically work but which are incompatible with each other.

Because there is no requirement of coherency, there are many solutions to the empirical foundationalist crossword puzzle. Here’s one:

The Coherentist Crossword Puzzle

Here is what that crossword puzzle looks like to a coherentist who rejects any notion of basic beliefs. The clues are blank, because all that matters is that the answers to the puzzle be coherent.

There are, again, many solution to the puzzles. Here’s one. It has no connection whatsoever to the clues we provided above, but it’s coherent.

Note the insoluble dilemma poised here. The empirical foundationalist will assert that the answer to 1 - Down can’t be “targets” because “targets” doesn’t mean “to cause upset.” The coherentist will reply that the answer to 1- Down can’t be “disturb” because it’s not coherent with “starfarts”. The Münchhausen skeptic will eat popcorn while they fight it out.

The Foundherentist Crossword Puzzle

The foundherentist crossword puzzle is the puzzle we first introduced. It looks like this:

The foundherentist can safely reject both the empirical foundationalist and the coherentist as wrong in their belief system. The answers “stargate” and “disturb” are not coherent with each other, and the answers “starfart” and “targets” are not correct given the clues. Instead, the foundherentist can assert that the popular space opera franchise must be “startrek” and that causing upset is to “provoke”.

But not so fast! A Jedi has appeared on scene, and he asserts there is another solution to the puzzle:

We are grudgingly forced to admit that “starwars” and “incense” are correct and coherent answers to the puzzle. Therefore we have two justified systems of belief that stand in direct contradiction to each other.

I would argue that is, in many ways, the world we live in. Half of the population has one set of beliefs, and the other half has another set of beliefs, and both belief systems are coherent internally but mutually exclusive.

Given this problem, how does the foundherentist proceed? There are two basic paths forward. The first path is to argue about the merits of the answers. “Given how badly the Star Wars sequels flopped with audiences, Star Wars cannot possibly be considered a ‘popular space opera franchise’ anymore!” This is, more or less, how people argue on the internet.

The second path is to broaden our inquiry, adding additional clues. That might look like this:

So now we can solve it! The Trekkers are right and the Jedis are wrong. The answers are “startrek” “provoke” and “pencil”.

Well, not so fast. The Jedis still have a justified system of belief! Their answers are “starwars” “incense” and “inkpen”.

And on it goes. But I do not think this is a flaw in my theory; rather, I believe, this is the proper way that human knowledge can and should be justified. With every question we ask, we learn more; and provided we keep at it, we will eventually converge on truth.

Indeed, the epistemological theory I have developed is already in actual use by scientists and engineers. As Alexander Marinos writes:

It comes with many names. Robotics calls it “sensor fusion”, hedge funds call it using “alternative data”, evolutionary psychology calls it “nomological networks of cumulative evidence”, social sciences call it “methodological triangulation”, astronomers call it “multi-messenger astronomy”, in biology it’s called “multisensory integration”, and in vision it’s called “parallax”.

The idea itself is very simple, though it took me a decade to absorb. If you’re worried about implementation issues in your sensors, use many different sensors. If you’re seeing something, your eyes may be playing tricks on you. But if you’re seeing, smelling, touching, and tasting something, well, at that point it’s not an artifact of your senses. It would be extraordinarily unlikely (read: impossible) for all your senses to misfire in the same way at the same time without some unifying cause, either in your brain, or in the world.

I cannot take credit for “inventing” any of these techniques. But I think I can take credit for developing an epistemological justification for them that is more than the strictly Bayesian one that Marinos relies on. Because what all of these techniques are relying upon, without realizing they’re relying upon it, is my axiom of evidence, the irrefutable proposition that the evidence of our senses is not entirely unreliable. (Again, it’s irrefutable because all of the evidence for the unreliability of our senses itself arises from the senses, such that a skeptic of sensory evidence can not even argue that the senses are totally unreliable because he’d have no evidence with which to do so, and even if he did have such evidence, he’d have no way to use it to refute a proposition, because that refutation could not be reliably made absent the senses.)

In summary:

We can defeat the Trilemma’s attack on foundationalism by establishing a foundation of irrefutable axioms that are noetically apprehended;

Because our irrefutable axioms include both the laws of logic and the axiom of evidence, we do not need to limit ourself to a rationalist foundationalism that leaves us unable to hold beliefs about the real world;

Because the axiom of evidence is only irrefutable to the extent that it applies to the totality of empirical evidence, we must require that all of our beliefs based on empirical evidence be coherent with each other;

The epistemological approach that meets this requirement is called foundherentism, and it is why, e.g. “methodological triangulation,” “nomological networks of cumulative evidence,” “multisensory integration,” and other techniques work.

I now consider the Trilemma defeated and will now move on to other philosophical challenges. In the future I might sketch out some implications of foundherentism, particularly with regard to how Leftist attempts to suppress free inquiry into controversial topics can now be understood for what they truly are, attempts to block foundherentist accumulation of knowledge that will render *their* crossword puzzle answers wrong.

But that’s for the future. For now, join me in exulting about this on the Tree of Woohoo!

Schrodinger's Cat may or may not disagree with some of your axioms.

You lost me when you mentioned BELIEFS is a discussion about EPISTEMOLOGY.

BELIEFS are DOXA, not EPISTEME.

DOXA is for Redditors and trans-activists - because there is no veridicality axiom.

[The ALLCAPS is not intended to indicate that I'm SHOUTING... it's meant to indicate that Substack's comment 'system' (sic) is retarded "HelloWorld"-level garbage coded by $7/hr gamma-monkeys.

$7/hr may not be literally true, but is framed as a relativity: Boeing paid $9/hr for the cretins who did the software for 737Max - and we know how that ended.]