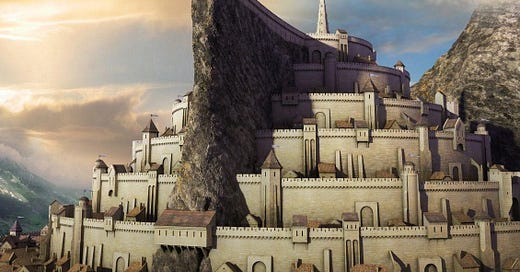

“For the fashion of Minas Tirith was such that it was built on seven levels, each delved into the hill, and about each was set a wall, and in each was a gate.” - J.R.R. Tolkien, The Return of the King

Freedom is always under siege from the roving bandits that seek to tyrannize and plunder the free. To protect themselves, the Founding Fathers of the United States erected the Constitution as a citadel of freedom. Like Minas Tirith, it was built with seven walls. From outer to inner, the walls are:

A written constitution.

A vertical separation of powers.

A horizontal separation of powers.

A government of enumerated powers.

A government of mixed type.

A bill of enumerated rights.

An acknowledgment of unwritten rights.

All seven walls have been breached, or worse — many of the gates were opened by naïve fools, would-be tyrants, and disloyal magistrates, or left unmanned by a decadent and distracted citizenry.

The Written Constitution

The Wall: A Constitution is essentially a compact or contract between citizens. Like a contract, a Constitution can be unwritten (verbal) or written. An unwritten contract has certain advantages. It can be put in place more easily. It can grow over time as the parties to the contract become familiar with each other. It can be amended to changing conditions with ease. But there are disadvantages as well. An unwritten contract relies on custom, tradition, and mutual self-interest. It is easy for differences of opinion to arise when unexpected situations develop, and difficult to determine how such differences should be resolved. It is also easy for the party with more bargaining power over time to constantly and quietly encroach on the other parties.

Great Britain, against which the Framers had rebelled, had an unwritten Constitution. The Framers adopted a written one. When the US Constitution was written, it closely approximated the unwritten British Constitution - the President had virtually identical powers to those held by the British king at that time; the Senate resembled the House of Lords; and the House of Representatives resembled the House of Commons, including its control over the purse (budget).

The Framers were very concerned about concentration of power and governmental overreach, and they felt that by explicitly writing down the government’s powers they could limit or avoid the flaws of an unwritten Constitution.

The Breaches: The wall was first breached in Marbury v. Madison (1803). This landmark U.S. Supreme Court case established the principle of judicial review in the United States, meaning that American courts have the power to strike down laws and statutes that they find to violate the Constitution of the United States. But this power is nowhere vested in writing in the Supreme Court!

Now, a Constitution does need an arm of enforcement, and the Framers had erred for not making it clear who and how violations of the Constitution would be addressed. The Supreme Court filled the gap, perhaps rightly so, but they did so with no constraint on their power, while at the same time claiming a monopoly over the Constitution.

The wall was breached for a second time in McCulloch v. Maryland (1819). In this case, the Court was reviewing the constitutionality of the Second Bank of the United States, which had been established by Congress to regulate the nation's money and credit. The state of Maryland argued that the Bank was unconstitutional because it was not specifically mentioned in the Constitution and that Congress did not have the power to create it. Relying on the power it had just assigned itself in Marbury, the Court upheld the constitutionality of the Bank, citing the Necessary and Proper Clause as the source of Congress's power to create it.

The Necessary and Proper Clause, also known as the Elastic Clause, is found in Article I, Section 8 of the United States Constitution and gives Congress the power "to make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing Powers, and all other Powers vested by this Constitution in the Government of the United States, or in any Department or Officer thereof." It has been used as a wedge to crack open the written constitution and add more and more unwritten power to the government.

However, the breaches caused by McCulloh and Marbury were small at first. During the entirety of the 19th century, the Supreme Court largely relied upon methods of interpretation that put the plain text and original meaning of the Constitution, and the intent its Framers, at the center of their arguments. (Even skeptics of originalism or textualism at least made the effort to justify their decisions on such bases.) As a result, most of the cases were argued and decided on the meaning of the text as it was understood at the time of its adoption. Obviously, if a written constitution is to undergo judicial review, this is the only method of judicial review which can maintain its fixed meaning.

Sadly, in the early 20th century, a group of progressive legal scholars and judges, men such as Holmes, Cardozo, Dewey, and Pound¹, began to argue that the Constitution should be interpreted in a more flexible and dynamic way, rather than being bound by the original meaning of the text, so that it could be “adapted” to changing social, economic, and political conditions and interpreted in a way that reflected contemporary values and ideals. After all, wasn't that Necessary and Proper? This philosophy became known as the "Living Constitution" and, by intent, it destroyed the solidity and fixedness which is the chief merit of a written constitution.

The “Living Constitution” remained a minority view until 1937, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt proposed to “pack the court” by expanding the size of the Supreme Court from nine justices to fifteen justices. Roosevelt sough to circumvent the Supreme Court's resistance to many of the New Deal programs and policies, resistance that arose from their originalist and textualist interpretations of the written Constitution.

Tragically, when faced with the threat of court-packing, the Supreme Court succumbed to cowardice. In the case West Coast Hotel vs. Parrish, in a moment known as “the Switch in Time that Saved Nine²,” the Supreme Court suddenly and dramatically adopted a “Living Constitution” approach to its jurisprudence. Since then, “Living Constitution” jurisprudence has created an unwritten Constitution that trumps the written word.

Today, the first wall has been utterly torn down. The merest glimpse at a Supreme Court case today reveals a twisting maze of jurisprudence only remotely connected to the text of the Constitution.

The Vertical Separation of Powers

The Wall: Vertical separation of powers is a means of implementing subsidiarity, the principle that government ought to reside at the lowest feasible level. Local issues should be handled by local government, not by national government. Local government, being both small and proximate, is more responsive to the needs of local people; by jealously guarding its power against the incursions of national government, local interests can be protected from the sort of tyranny discussed in the book Seeing Like a State.

This second wall was built less strongly than it might have been, because during the prior Articles of Confederation, the national government had been too weak. The Founding Fathers were keenly aware that they were taking a risk by building this wall weakly. In the leadup to the ratification, Federalist Paper 44 explained why the national government had to be (relatively) strong; and Federalist Paper 46 explained why it wasn’t too strong.

The argument in Federalist Paper 46 turned on the fact that the federal government would not have a standing army. Hamilton wrote:

The only refuge left for those who prophesy the downfall of the State governments is the visionary supposition that the federal government may previously accumulate a military force for the projects of ambition…

That the people and the States should, for a sufficient period of time, elect an uninterupted succession of men ready to betray both; that the traitors should, throughout this period, uniformly and systematically pursue some fixed plan for the extension of the military establishment; that the governments and the people of the States should silently and patiently behold the gathering storm, and continue to supply the materials, until it should be prepared to burst on their own heads, must appear to every one more like the incoherent dreams of a delirious jealousy, or the misjudged exaggerations of a counterfeit zeal, than like the sober apprehensions of genuine patriotism. Extravagant as the supposition is, let it however be made…

Let a regular army, fully equal to the resources of the country, be formed; and let it be entirely at the devotion of the federal government; still it would not be going too far to say, that the State governments, with the people on their side, would be able to repel the danger. The highest number to which, according to the best computation, a standing army can be carried in any country, does not exceed one hundredth part of the whole number of souls; or one twenty-fifth part of the number able to bear arms. This proportion would not yield, in the United States, an army of more than twenty-five or thirty thousand men. To these would be opposed a militia amounting to near half a million of citizens with arms in their hands, officered by men chosen from among themselves, fighting for their common liberties, and united and conducted by governments possessing their affections and confidence. It may well be doubted, whether a militia thus circumstanced could ever be conquered by such a proportion of regular troops…

Besides the advantage of being armed, which the Americans possess over the people of almost every other nation, the existence of subordinate governments, to which the people are attached, and by which the militia officers are appointed, forms a barrier against the enterprises of ambition, more insurmountable than any which a simple government of any form can admit of. Notwithstanding the military establishments in the several kingdoms of Europe, which are carried as far as the public resources will bear, the governments are afraid to trust the people with arms. And it is not certain, that with this aid alone they would not be able to shake off their yokes. But were the people to possess the additional advantages of local governments chosen by themselves, who could collect the national will and direct the national force, and of officers appointed out of the militia, by these governments, and attached both to them and to the militia, it may be affirmed with the greatest assurance, that the throne of every tyranny in Europe would be speedily overturned in spite of the legions which surround it. Let us not insult the free and gallant citizens of America with the suspicion, that they would be less able to defend the rights of which they would be in actual possession, than the debased subjects of arbitrary power would be to rescue theirs from the hands of their oppressors. Let us rather no longer insult them with the supposition that they can ever reduce themselves to the necessity of making the experiment, by a blind and tame submission to the long train of insidious measures which must precede and produce it.

The Anti-Federalists were not entirely convinced by the arguments (nor should they have been.) and so when the Constitution was enacted, the 10th Amendment was added to buttress this wall. The 10th Amendment stated, “The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the states, are reserved to the states respectively, or to the people.”

The Breaches: The first breach came in McCulloch v. Maryland (1819), when the Supreme Court ruled that federal laws trump state laws. In McCulloch, Congress had established a national bank and Maryland had put a tax on the national bank. Maryland argued that the Constitution gave no power to the federal government to establish a national bank, and placed no limit on the states taxing banks. The Supreme Court (now the primary gatekeeper of Fortress America’s walls) ruled against Maryland. McCulloch established the principle of federal supremacy and paved the way for the demolition of the vertical separation of powers. (Chief Justice Marshall did not intend for the decision to be interpreted as broadly as it later was, but that was the outcome all the same.)

The second breach came as a result of the American Civil War. Whatever one cares to think of the origin and outcome, it is a matter of empirical fact that before the Civil War, one would say “the United States are doing such-and-such” and that after the Civil War, one would say “the United States is doing such-and-such.” That is: The Union became a unity, secession an impossibility, and the concept of state’s rights was thereafter defanged.

The third breach came in U.S. vs Darby (1941). Under Roosevelt’s New Deal, Congress had passed the Fair Labor Standards Act, which set a minimum wage and maximum hours for all workers involved in interstate commerce. The defendant Darby violated the FLSA and was taken to court by the government. Although the lower courts all found the act unconstitutional, because the federal government was not permitted to regulate intrastate activities, the Supreme Court ruled that it was constitutional. Henceforth, Congress could not just regulate interstate commerce, but all activities relating to interstate comments.

Today, Congress asserts the power to regulate anything it wishes. If the Necessary and Proper clause was the wedge in the crack, the Commerce Clause has become the lever on the wedge. Only a handful of Supreme Court justices, most notably Justice Clarence Thomas³, bother to fight against this precedent, and their wins have been few and far between. In his famous opinion in U.S. vs. Lopez, Thomas wrote:

In addition to its powers under the Commerce Clause, Congress has the authority to enact such laws as are "necessary and proper" to carry into execution its power to regulate commerce among the several States. But on this Court's understanding of congressional power under these two Clauses, many of Congress' other enumerated powers under Art. I, § 8, are wholly superfluous.

After all, if Congress may regulate all matters that “substantially affect” commerce, there is no need for the Constitution to specify that Congress may enact bankruptcy laws, cl. 4, or coin money and fix the standard of weights and measures, cl. 5, or punish counterfeiters of United States coin and securities, cl. 6. Likewise, Congress would not need the separate authority to establish post offices and post roads, cl. 7, or to grant patents and copyrights, cl. 8, or to "punish Piracies and Felonies committed on the high Seas," cl. 10. It might not even need the power to raise and support an Army and Navy, cls. 12 and 13, for fewer people would engage in commercial shipping if they thought that a foreign power could expropriate their property with ease.

Indeed, if Congress could regulate matters that substantially affect interstate commerce, there would have been no need to specify that Congress can regulate international trade and commerce with the Indians. As the Framers surely understood, these other branches of trade substantially affect interstate commerce.

Put simply, much if not all of Art. I, § 8 (including portions of the Commerce Clause itself), would be surplusage if Congress had been given authority over matters that substantially affect interstate commerce. An interpretation of cl. 3 that makes the rest of § 8 superfluous simply cannot be correct. Yet this Court's Commerce Clause jurisprudence has endorsed just such an interpretation.

Thomas is entirely correct, both about the Court’s interpretation and its implication. The second wall has fallen. It is dust. Indeed, the very militia that Hamilton believed would protect the states from the federal government is now under federal control in the form of the National Guard.

3rd Wall: The Horizontal Separation of Powers

The Wall: The horizontal separation of powers is a system by which the powers of government are divided among different branches, each with its own separate and independent areas of responsibility.

The concept of the separation of powers can be traced back to ancient Greek and Roman philosophers, but it was first articulated in its modern sense by the French philosopher Montesquieu in his work "The Spirit of the Laws," published in 1748. Montesquieu argued that a government in which the powers of the different branches are divided and checked against one another is better able to protect the liberties of its citizens. He also believed that the separation of powers would help to prevent the abuse of power by any one branch of government.

Montesquieu's ideas about the separation of powers had a significant influence on the founders of the United States, who included the principle in the Constitution as a way to prevent the concentration of power in the hands of a single branch of government and to protect the liberties of American citizens. Under the U.S. Constitution, the three branches are the legislative, executive, and judicial branches. The legislative branch, made up of the Senate and the House, is responsible for creating and passing laws. The executive branch, made up of the President, the Vice-President, the Cabinet, and their subordinates, is responsible for enforcing the laws. The judicial branch, made up of the federal District, Appeals, and Supreme Courts, is responsible for interpreting the laws and deciding cases that involve disputes over the meaning or application of the laws.

In the 20th century, the horizontal (and vertical) separation of powers was able defended by political philosopher James Burnham. According to Burnham, power is an inherent part of any political system, and it is impossible to eliminate power completely. Instead of trying to eliminate power, Burnham argued that it is more effective to use power to oppose and balance other sources of power. Each part of government would have a vested interest in expanding its own power at the expense of the others, and they would keep each other in check.

Despite its storied history, horizontal separation of powers is not present in most democracies today. In parliamentary systems, such as those found in the United Kingdom and many other countries, the executive branch of government is appointed and can be removed by the legislative branch. In semi-presidential systems, such as those found in France and many other countries, there is both a president and a prime minister. The president is elected directly by the people and is responsible for appointing the prime minister and cabinet, while the prime minister is still responsible to the legislative branch. In both systems, the executive branch is more closely accountable to the legislative branch than in a system with a horizontal separation of powers. Proponents of these systems argue that the separation of power makes it too difficult for government to act quickly and leads to gridlock. Most of them favor large, powerful governments and have little time for Montesquieu and Burnham. They don’t want this wall to exist.

The Breach: The third wall was breached in Yakus v. United States (1944). In Yakus, the Supreme Court was asked to review the constitutionality of price controls that had been issued by the War Labor Board, an administrative agency, during World War II. The petitioner in Yakus argued that the price controls violated the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment because they were issued by an administrative agency, rather than by Congress.

The Court rejected this argument, holding that when the War Labor Board imposed price controls, this was a valid exercise of Congress's power — despite the fact that the WLB was part of the executive branch! In doing so, it relied on the precedent of U.S. vs Darby (1941), which had torn down the second wall a few years earlier. Based on Darby, the Court held that Congress had the power to impose price controls nationwide under the Commerce Clause. It then held that, since Congress had the power to pass the law, it could delegate that power to an administration agency. Here, the Court relied on the “Necessary and Proper” clause jurisprudence that had brought down the second wall: Delegation is a “necessary and proper” way for Congress to address complex and technical issues that require specialized expertise.

But if the branches of government can delegate their power to each other, then there is no separation of power… and today there is not. The breach in the third wall was made possible by the breaches in the first and second wall; and once made, it proved irreparable.

Nowadays, there are thousands of administrative agencies, and the vast majority of federal lawmaking takes place in the executive branch, rather than the legislative branch. Indeed, the administrative agencies are today so powerful that many refer to them as the fourth branch of government or the deep state.

Next week, we’ll continue our military history of Fortress America and its seven walls. In the meantime, join me in contemplating the siege on the Tree of Woe.

Note: For unknown reasons, Substack failed to save part of the essay and as a result a prior draft was published. I have updated the text with the correct version. The section on the first wall is now much more detailed. Sorry for the inconvenience!

Wow! You have convinced me that I need to finally get around to reading the Federalist Papers. I had no idea that Alexander Hamilton endorsed private gun ownership as a check on the federal government. I always associated that with Jefferson.

---

Regarding vertical separation: I have come to the conclusion that the reason the Democrats have become such serious centralists is that for Blue America, there is no such thing as local government. If you live in a county or city with 200,000+ people, your local government isn't really local. And since the federal government does have better rule of law than many city governments, federal bureaucrats -- and criminal gangs -- are more responsive than the titular local government. "You cannot fight City Hall"

Maybe the solution is to leverage the sentiments that launched BLM and Antifa and give those "anarchists" what they were truly asking for: local government. Do a bit of "formalizing" as Mencius Moldbug would put it.

Much more here:

https://rulesforreactionaries.substack.com/p/rule-6-break-up-the-blue-zones

(Warning: it's a five-parter.)