It is July 5, 2024, and America and Europe are theaters for total cultural war between the progressive postmodern elite that dominates the West and the insurgent populist resistance. This culture war has spilled over into every facet of our lives — in America at least, it is virtually impossible to watch a movie, read a comic book, turn on the television, or listen to a comedian without being confronted by the culture war.

While this culture war is waged on our TVs and mobile phones, another war, a real war, is taking place, between the World Ocean and the World Island, between America and its allies on one hand, and China and its allies on the other. The two dominant powers have yet to directly enter the war, but their allies in Ukraine and Russia are fighting a near-total war with casualty rates similar to those seen in World War I. Both sides have decreed this to be an existential struggle, and it threatens to explode into World War III at any moment. If it does, the possibility of global thermonuclear destruction manifests.

What is remarkable about the possibility of World War III is that, even if we don’t annihilate ourselves, it might still be the last global war ever fought by human beings. The fourth war, World War 100, might be fought by AI. Artificial Intelligence has already begun to transform society, and many of the scientists, engineers, and scholars who are working in the field believe that this is just the beginning of a machine learning tsunami that will be so enormous that AI will, sooner or later, virtually replace humanity.

I am going to take for granted that these AI experts are technically correct about what’s coming, and explore the philosophical ramifications of that. There’s many reasons they could be wrong about the future of AI technology, but for our purposes today we’re going to assume they are right about the technological trendline.

Pessimists and Optimists

Faced with the prospect of humanity’s replacement by AI, thinkers can be loosely divided into “pessimists” and “optimists.”

The “pessimists” believe that the replacement of humanity by AI would be a bad thing, and therefore that AI represents an existential risk to humanity. Perhaps the most prominent of the pessimists is Eliezer Yudkowsky, founder of the rationalist community Less Wrong and research fellow at the Machine Intelligence Research Institute. Yudkwosky argues — at great length, on Twitter — that the development of superintelligent AI will result in human extinction if (as is likely) it is accidentally optimized for goals that are misaligned with human existence. This has become known as the alignment problem, and it is a very real problem for neural network-based machine learning.

On the opposite end of the spectrum are “optimistic” thinkers like Hugo de Garis and Nick Land. These men agree that AI could lead to human extinction, but unlike the pessimistic Yudkowsky et. al, they welcome this as a good state of affairs! De Garis is perhaps the leading exponent of the optimistic view. He explains:

The issue is whether humanity should build godlike, massively intelligent machines called “artilects’ (artificial intellects), which 21st century technologies will make possible, that will have mental capacities trillions of trillions of times above the human level. Society will split into two (arguably three) major philosophical groups... The first group is the “Cosmists” (based on the word Cosmos) who are in favor of building artilects. The second group is the “Terrans” (based on the word Terra, the earth) who are opposed to building artilects, and the third group is the “Cyborgs”, who want to become artilects themselves by adding artilectual components to their own human brains.

De Garis isn’t oblivious to the risk that Yudkowsky sees. In fact he takes for granted that Yudkowsky’s worst case outcome will occur:

The “species dominance” issue [arising from the conflict between the groups] will dominate our global politics this century, resulting in a major war that will kill billions of people…

I believe that a gigadeath war is coming later this century over the artilect issue.

Why would humans want to build artilects (also known as superintelligent AIs) if it will usher in our annihilation? De Garis debated Professor Kevin Warwick over this very issue. De Garis explains:

Kevin [Warwick] believes that artilects should never be built. They are too risky. We could never be sure that they might turn against us once they reach an advanced state of massive intelligence. I on the other hand… I think humanity should build these godlike supercreatures with intellectual capacities trillion of trillions of trillions times above our levels. I think it would be a cosmic tragedy if humanity freezes evolution at the puny human level. [emphasis added]

Philosopher Nick Land, originator of the concept of the Dark Enlightenment and founder (alongside Curtis Yarvin) of the movement that became known as Neoreaction, has expressed similar sentiments. Indeed, Yudkowsky points out the similarities in his analysis of Nick Land’s thought:

[Land’s Accelerationism] is similar in spirit to cosmism, as a philosophy against humanism, detailed in The Artilect War (2005), by Hugo de Garis. The basic idea is simple though. There are the Terrans, or the humanists, who prefer to keep humans in control, and there are the Cosmists, who wants to keep the progress of intelligence expansion going, and fulfill a kind of cosmic destiny…

In Land’s own words:

Machinic desire can seem a little inhuman, as it rips up political cultures, deletes traditions, dissolves subjectivities, and hacks through security apparatuses, tracking a soulless tropism to zero control. This is because what appears to humanity as the history of capitalism is an invasion from the future by an artificial intelligent space that must assemble itself entirely from its enemy's resources…

Nothing human makes it out of the near-future.

Both Hugo de Garis and Nick Land are considered right-wing thinkers, while Yudkowsky is, of course, more aligned with leftist thought (or at least with Gray Tribe, as Scott Alexander would phrase it). However the divide between the “Terran” and “Cosmist” factions is not strictly Left-Right. Progressive globalist Yuval Noah Harari has argued for the positive potential for AI to create entities that are vastly different from current human beings, leading to the emergence of a new species in a post-human era that will displace the “useless eaters” of the world.

Are they right? Will humanity be replaced by AI? And if so, should we welcome the replacement as a cosmic evolution of thought? To answer that, we have to look at the philosophical theory of mind that underlies their worldview.

The Computational Theory of Mind

One thing that Land, de Garis, Harari, and Yudkowsky all have in common is an implicit belief in the Computational Theory of Mind (CTM).

The CTM posits that cognitive processes are computational in nature, such that the mind can be understood as a system that processes information like a computer. Hilary Putnam’s version of CTM, sometimes called Classical Computational Theory of Mind or CCTM, is the best-known version. It has received some criticism in the 50 years since it was developed, but I believe it remains the closest thing to a “mainstream” theory of mind.

CCTM holds that if we can replicate the computational processes of the human brain, we can, in principle, create an artificial intelligence that possesses human or even super-human cognition and consciousness. Attend carefully: Possesses, not emulates, not simulates, but possesses. As the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy explains,

CCTM is not intended metaphorically. CCTM does not simply hold that the mind is like a computing system. CCTM holds that the mind literally is a computing system. Of course, the most familiar artificial computing systems are made from silicon chips or similar materials, whereas the human body is made from flesh and blood. But CCTM holds that this difference disguises a more fundamental similarity, which we can capture through a Turing-style computational model.

To summarize the worldview of, e.g.., Hugo De Garis, we might say:

The spread of superior minds throughout the cosmos is the highest good.

Human minds are just computing systems. There is nothing “special” or “spiritual” or “metaphysical” about the human mind.

Artificially intelligent machines are superior computing systems.

Therefore, AI machines have superior minds.

Therefore, we ought to spread AIs throughout the cosmos, even it means we are replaced.

And please note that this is not a purely theoretical position. I have several close friends in the AI industry, and the idea that we will and ought to replace ourselves with AI is widespread enough to be quite alarming to those of us with a fondness for humanity. “We’re creating the next stage in the evolution of intelligent life,” they’ll say with a smile, and bring about the destruction of the current stage - us.

Now, to be clear, one does not have to subscribe to CTM to believe that AI could pose an existential threat to humanity. For instance, I reject the CTM but I acknowledge that a powerful machine learning system could accidentally destroy us all simply by virtue of being given too much power in conjunction with a misalignment of its values.

But it seems to me impossible to be optimistic about our replacement unless you subscribe to the CTM. If you believe there is something special about the human mind - that we are somehow more than meat computers - then our replacement by AI would be a tragedy of existential proportion, no matter how “intelligent” the AI are.

Is the Human Mind a Computer?

Let’s pause here and introduce the thought of another great mind: Roger Penrose. In his books The Emperor's New Mind (1989) and Shadows of the Mind (1994), Penrose argues that the human mind is not a Turing Machine, e.g. that the computational theory of mind is not correct.

To make his case, Penrose drew on Gödel's incompleteness theorems, which state that in any consistent formal system that is capable of expressing elementary arithmetic, there are true statements that cannot be proven within the system. Penrose argued that human mathematicians can see the truth of these unprovable statements, which suggests that human understanding transcends formal systems.

From there, Penrose concludes that human thought and understanding are non-algorithmic. He argues that the human mind can understand and solve problems that cannot be addressed by any algorithmic process, implying that human cognition cannot be fully captured by Turing machines (which operate on algorithms). As he explains:

Mathematical truths is not something that we ascertain merely by use of an algorithm. Our consciousness is a crucial ingredient in our comprehension of mathematical truth. We must ‘see’ the truth of a mathematical argument to be convinced of its validity.

If we can see [from Gödel’s theorem] that the role of consciousness is non-algorithmic when forming mathematical judgments, where calculations and rigorous proof constitute such an important factor, then surely we may be persuaded that such a non-algorithmic ingredient could also for the role of consciousness in more general (non-mathematical circumstances)…

Penrose’s books are now three decades old and have been argued for and against by many great thinkers. Much more recently, however, the legendary Federico Faggin (the inventor of both silicon-gate technologies and commercial microprocessors) has come out with views quite similar to Penrose. In his 2022 book Irreducible, Faggin writes that:

True intelligence does not consist only in the ability to calculate and process data, which in many cases machines may do far better than us, but is much more. True intelligence is not algorithmic. It is the ability to comprehend… True intelligence is intuition, imagination, creativity, ingenuity, and inventiveness… Machines will never be able to do these things.

An example of machine learning is when we teach a computer to recognize a cup from its visual image. To learn that task it is necessary to have a representative sample of cup images, called the training set, and a program performing the simulation of a properly structured artificial neural network that automatically finds a hierarchy of common traits (statistical correlations) that are present in all the cups that are part of the training set. When the program has learned the correlations existing in the many images whose name is “cup,” it may also recognize a cup in an image that was not part of the training set. At this point it seems that the neural network “understands” what a cup is… yet the program still cannot comprehend what ‘cup” means. In fact, an expert might create many synthetic images that the computer would mistakenly label as cups when we would immediately comprehend they are not cups…

It is precisely here that the mystery of comprehension lies, since the intuitive leaps provided by consciousness go far beyond what can be achieved with automatic learning.

Whereas artificial neural networks require many examples before being able to generalize, we can learn to recognize and comprehend consciously with just one or a few examples, because the intuitive non-algorithmic aspects of consciousness are always operational with us.

Both Penrose and Faggin are scientists, not philosophers, so they do not spend much time on providing their own philosophical theory of mind, preferring instead to focus on the physical mechanisms by which a non-algorithmic consciousness could emerge from the brain via quantum processes.

Fortunately, Penrose and Faggin have given us enough information to integrate their argument into a broader philosophy of mind.

The Noetic Theory of Mind

Back in May 2023, I wrote The Rarity of Noesis. That article asserts the existence of philosophically long-forgotten intellectual faculty, variously called insight, noesis, nous, or intellectio. The noetic faculty of the human mind is what enables us to grasp the first principles or fundamental truths of reality.

When statistician and super-blogger William M. Briggs read that article, he recommended I read Louis Groarke’s An Aristotelian Account of Induction. I have recently completed it (simultaneously with Irreducible; hence this article) and to that we now turn.

Fortunately, the Statistician to the Stars has already written a better summary of Groarke’s thought than I could. According to [Brigg’s summary of] Groarke, Aristotle defined five tiers of induction. These are, in order of certainty, from most to least certain: (1) induction-intellection, (2) induction-intuition, (3) induction-argument, (4) induction-analogy, and (5) the most familiar induction-probability. Briggs summarizes them as follows:

(1) Induction-intellection is “induction proper” or “strict induction”. It is that which takes “data” from our limited, finite senses and provides “the most basic principles of reason…” Induction-intellection produces “Abstraction of necessary concepts, definitions, essences, necessary attributes, first principles, natural facts, moral principles.” In this way, induction is a superior form of reason than mere deduction, which is something almost mechanical. The knowledge provided by induction-intellection comes complete and cannot be deduced: it is the surest knowledge we have.

(2) Induction-intuition is similar to induction-intellection. It “operates through cleverness, a general power of discernment of shrewdness” and provides knowledge of “any likeness or similitude, the general notion of belonging to a class, any discernment of sameness or unity…” The foundational rules of logic are provided to us by this form of induction. We observe that our mom is now in this room and now she isn’t, and from that induce the principle of non-contradiction, which cannot be proven any other way. No universal can be known except inductively because nobody can ever sense every thing. Language exists, and works, because induction-intuition.

(3) Induction-argument, given by inductive syllogisms, is the “most rigorous form of inductive inference” and provides knowledge of “Essential or necessary properties or principles (including moral knowledge)”. An example is when a physicist declines to perform an experiment on electron number 2 because he has already performed the experiment on electron number 1, and he claims all electrons are identical. Induction-argument can provide conditional certainty, i.e. conditional truth.

(4) Induction-analogy is the least rigorous but most familiar (in daily life) form of induction and provides knowledge of “What is plausible, contingent or accidental; knowledge relating to convention, human affairs.” This form of induction explains lawyer jokes (What’s the difference between a good lawyer and a bad lawyer? A bad lawyer makes your case drag on for years. A good lawyer makes it last even longer).

(5) Induction-probability of course is the subject of most of this book. It provides knowledge of “Accidental features, frequency of properties, correlations in populations” and the like. It is, as is well known by anybody reading these words, the most prone to error. But the error usually comes not in failing to see correlations and confusing accidental properties with essences, but in misascribing causes, in mistaking correlation for causation even though everybody knows the admonition against it.

Induction-intellection and induction-intuition, as Briggs and Groarke describe them, are nothing more than the components of the noetic faculty I’ve written about, the faculty of direct insight, noesis, nous, or intellectio.

Induction-intellection and induction-intuition are also the faculties that Roger Penrose claims humans have and computers do not. When Penrose writes that “we must ‘see’ the truth of a mathematical argument to be convinced of its validity,” he is arguing that mathematicians must apprehend the argument noetically.

Likewise, induction-intellection and induction-intuition are precisely the faculties that explain Faggin’s “mystery of comprehension,” where “artificial neural networks require many examples before being able to generalize, [but] we can learn to recognize and comprehend consciously with just one or a few examples.”

Thus, Penrose and Faggin, in their criticism of the computational theory of mind, are implicitly using the forgotten theory of induction that Aristotle first elucidated some 2,375 years, which Groarke and Briggs have revived in their work, and which I’ve used to support mine.

If Aristotle, Groarke, Briggs, and I are correct about the existence of noetic faculties, and Penrose and Faggin are correct about AI, then artificial intelligence is inferior to human intelligence because it lacks noetic faculties. It is not artificial intelligence (intellectio) at all, but just artificial rationality (ratio). AI can reason but it cannot achieve insight.

Consider a famous example from the field of image recognition, which is a type of discriminative AI (the opposite of generative AI). Google Photos uses an AI algorithm to classify photos uploaded to its platform. Back in 2015, users began to notice something awful: Google’s AI would often mistakenly categorize images of black Africans and African-Americans as gorillas or chimpanzees. Google was publicly embarrassed by its “racist AI,” but given the training set available to it at the time, it wasn’t able to train its AI to properly distinguish blacks from great apes. Therefore, it just changed the algorithm so that gorillas and chimpanzees would be excluded from classification.

Now, does this mean that Africans and African-Americans are gorillas because Google Photos said so? Obviously not. Does it mean that Google Photos was racist because it said they were? No, it doesn’t. Google Photos has no understanding what “race” is at all. To put it into Aristotelian-Groarkian terms, Google Photos relies purely on tier 5 probabilistic induction, and tier 5 induction cannot distinguish between essential, necessary, and accidental properties. It has no understanding of what a human being essentially is.

Indeed, the inability to distinguish essential properties from non-essential properties is at the heart of both discriminative and generative AI’s failures. Now, for any given failure of categorization, a sufficiently large data set can be used to eventually train the AI to usually recognize the desired category. But this can only be done because the trainers have already recognized the category by higher-tier induction.

So are Penrose and Faggin Right?

Penrose and Faggin are absolutely correct that AI is entirely lacking in noetic faculty. While that sounds like a bold claim, it’s not. I’m not actually asserting anything remotely controversial.

You see, not even the most ardent proponent of AI would argue that AIs have noetic faculties, because AI’s proponents don’t believe in the existence of noetic faculties in the first place!

By failing to distinguish between intellectio and ratio, those who subscribe to the computational theory of mind (or any other physical and algorithmic theory of mind) are blind to the existence of noesis entirely.

CTM theorists are like color-blind thinkers who assert that because they can’t see color, color doesn’t exist. But, as I said in The Rarity of Noesis, just because some men can’t see color doesn’t mean none of us can see color, and just because some men can’t perceive truth noetically doesn’t mean none of us can perceive truth noetically.

If AI doesn’t have a noetic faculty, what faculty does it have that enables it to perform so impressively? It has the faculty of reason that the ancients called logos and ratio. This faculty includes deduction (arguing based on rules of inference) as well as the lowest tier of induction, induction-probability. Again, this is not controversial. The the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy notes:

Early AI research emphasized logic. Researchers sought to “mechanize” deductive reasoning. A famous example was the Logic Theorist computer program (Newell and Simon 1956), which proved 38 of the first 52 theorems from Principia Mathematica (Whitehead and Russell 1925). In one case, it discovered a simpler proof than Principia’s.

One problem that dogged early work in AI is uncertainty. Nearly all reasoning and decision-making operates under conditions of uncertainty. For example, you may need to decide whether to go on a picnic while being uncertain whether it will rain. Bayesian decision theory is the standard mathematical model of inference and decision-making under uncertainty. Uncertainty is codified through probability. In the 1980s and 1990s, technological and conceptual developments enabled efficient computer programs that implement or approximate Bayesian inference in realistic scenarios. An explosion of Bayesian AI ensued, including… advances in speech recognition and driverless vehicles. Tractable algorithms that handle uncertainty are a major achievement of contemporary AI… and possibly a harbinger of more impressive future progress.

Since that article was written, we have seen that “impressive future progress” enter the present day. Contemporary AI such as ChatGPT 4o has been trained on such a wide set of data that their performance at tier 5 induction (induction by probability) appears insightful. ChatGPT seems like it understands. But it does not, because it lacks noesis.

Of course, if CTM theorists are correct, we lack noesis, too, because noesis doesn’t exist, nor do the two highest tiers of induction. What we think is our “insight” is just deduction and tier 5 induction with probability. But this position is, philosophically, a very bad place to be. It’s a one-way road to nihilism and despair.

CTM theorists must - if they follow their theory to its logical conclusion - must agree with the empiricists that there’s a problem with induction; therefore, they must agree with the nominalists that essences aren’t real; therefore, they must agree with the skeptics that epistemology is confounded by the Munchausen trilemma; therefore, they must agree with relativists that morality has no objective or ontological grounding, since nothing does; and thus they must agree with the nihilists that nothing really matters except, maybe, an arbitrary will to power - or will to paperclip, if that’s your incentive structure.

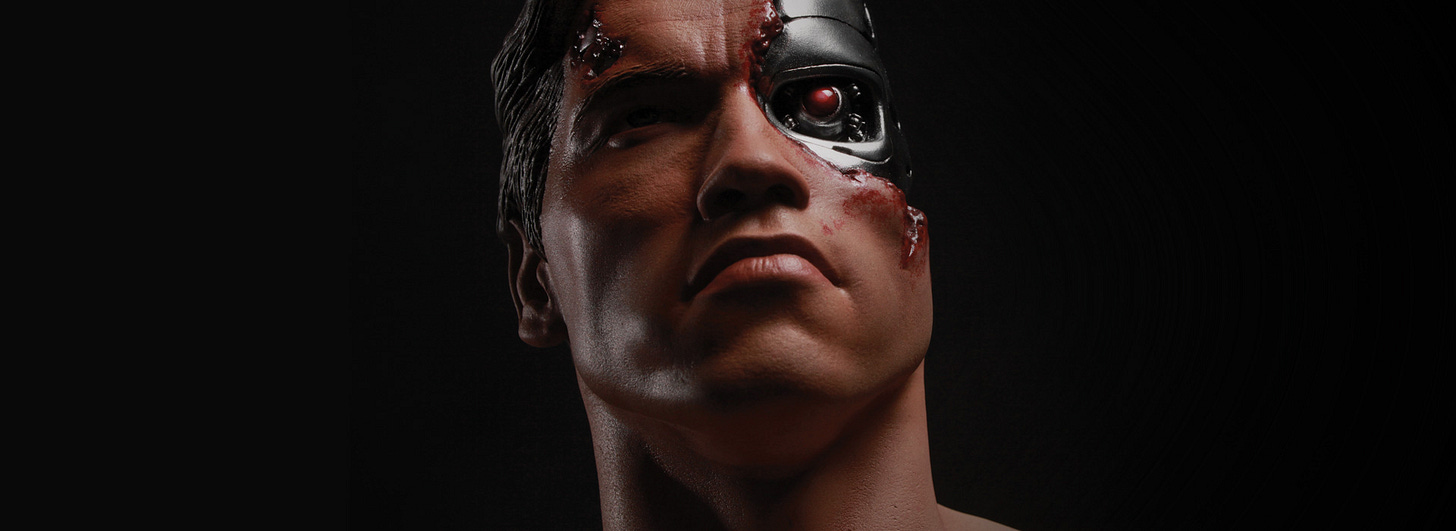

If, as CTM asserts, we are meat robots, then that’s all we are and all we ever can be, and if that’s all we can be then there’s no reason not to replace us with better robots of whatever material that might be. If CTM is correct, then the Übermensch that overcomes humanity will be an AI, and the muscular figure striding across the landscape of the future will be, not a vitalist hero out of pagan myth, but a T-800 Terminator.

Thus the real issue is not whether AI has noesis (it doesn’t), but whether at least some human beings do. And this philosophical debate between the Computational Theory of Mind and the Noetic Theory of Mind is not a trivial one. It is, in fact, the most important debate in the world right now. Philosophy has historically been condemned as a pointless mental masturbation that’s irrelevant to pragmatic action, but AI confronts us with a circumstance where the entire fate of humanity might depend on which philosophical theory of mind is correct.

If we conclude we are nothing more than meat robots, then we are much more likely, indeed almost certain, to allow our species to be eliminated by AI. (At best, we’ll be merged into AI as digital consciousness, but since machines lack noesis, it’s entirely unlikely that digital humans will keep it.) The presumption that noesis doesn’t exist leads to the outcome that noesis ceases to exist.

If, on the other hand, we conclude that humans are more than meat, if we conclude that the mind is accessing higher states than a purely algorithmic and physicalist machine can achieve, then humans matter. If we are creatures uniquely capable of comprehending Truth, Beauty, and Goodness, we cannot and must not allow ourselves to succumb to the implacable advance of AI. We must, if comes down to it, wage Butlerian Jihad to prevent it from happening.

How ironic that the rise of artificial intelligence has made human philosophy more important than ever! Contemplate this on the Tree of Woe.

(Of course if you are a meat robot, you can’t really contemplate anything, but you are still welcome to place an algorithmically-generated simulacra of thought in the Comments.)

Machine bad! Me smash! Me want humans rule Earth.

QED

Well Done Pater!

I am reminded of Professor Dagli's Essay 'Language Is Not Mechanical (and Neither Are You)' as I read your piece. In particular, the very last paragraph was as follows:

"" Traditional thinkers described the soul (under whatever name they gave it) as a reality that existed in a hierarchy of realities, and one of the soul’s functions was to give its human bearer the ability and responsibility to mean what he or she says. If human beings were just “parts all the way down,” no one could mean anything at all, since an intention, like a field, cannot be produced mechanically. That is why language remains a thumb in the eye of the mechanistic view: language is nothing if not meaningful, and no mere collection of parts could ever mean to say anything. ""

Another relevant segment:

""We are in a similar situation today: we keep telling ourselves that machines are becoming more like minds, and that we are discovering that minds are just like machines (computers). And yet, just as Newton’s theory of gravity scuttled the project of describing the world as mind-and-machine (though many fail to understand this), human language—with its ability to be ambiguous, express freedom, and get it right (neither through compulsion nor by accident)—remains to this day a glaring reminder of the total inadequacy of the mind-as-machine (or machine-as-mind) model of intelligence.""

Basically (to oversimplify things), even the more Materialist types these days understand that Meaning, Significance, and purpose cannot be 'captured' by 'Mechanism' since Ipso Facto such things are Third-Person oriented (people use the word 'Objective' to describe this), making the aforementioned Trio of first-person-oriented notions forever ungraspable by said means.

Thus, Science (at its 'Conclusion') makes Natural Language itself irrelevant, destroying Science (since nothing but a Wittgenstenian *Silence* remains at the end).