The Physiocratic Platform: Banking

How to End the Fed and Eliminate Fractional-Reserve Banking

I wanted to open this post by extending my gratitude to everyone who took the time to comment or email in response to my last post. I tried to respond to everyone but at a certain point the volume of commentary became so high that I lost the struggle. Nevertheless, I read everything. Thank you all for your kind words, suggestions, and ideas.

One of the comments I received was a suggestion that I needed to offer concrete platforms for Physiocracy. That suggestion was well-made as I presently have offered the framework for a political-economic platform but not the platform itself.

Today’s essay is therefore an exploration of the first plank of the physiocratic platform: ending the Federal Reserve System, escaping the petrodollar, and eliminating fractional-reserve banking. In order to understand today’s essay, you need some familiarity with those systems; please refer to Running on Empty I and Running on Empty II if you need a refresher.

Why is Banking the First Plank of Physiocracy?

Banking is the first plank of physiocracy’s platform for two reasons: the proximate urgency for reform and the proximate viability of reform.

The first time economists seriously challenged the orthodox monetary economics of their day was in the decades after the Great Depression. Those years saw a surge in heterodox economic thought as top scholars sought to decipher the glaring flaws in the prevailing economic framework. The debate spanned various sectors, but monetary economics took center stage due to the pivotal roles both private banks and central bank policies played in both igniting and prolonging the downturn.

In this period, many prominent U.S. macroeconomists rallied behind a significant monetary reform idea that came to be called the Chicago Plan. This was chiefly endorsed by professor Henry Simons from the University of Chicago and was eloquently distilled by Irving Fisher from Yale University in 1936. The Chicago Plan would have converted the United States to a full-reserve banking system where the money supply was controlled by the US Treasury. It would have brought an end to our debt money and fractional reserve system, and thereby prevented the perfidious petrodollar from ever being created.

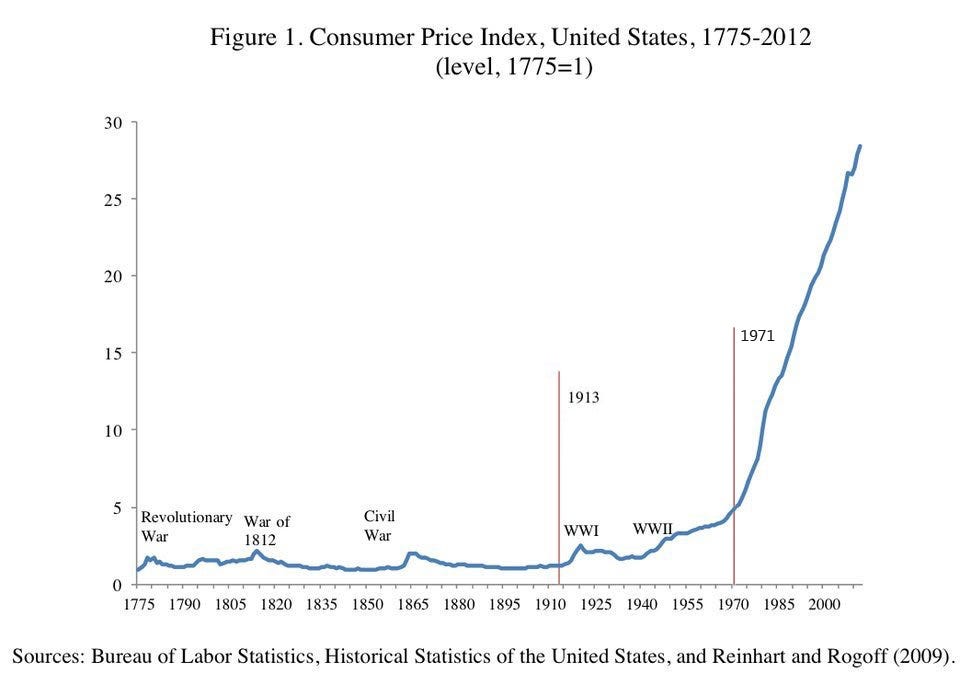

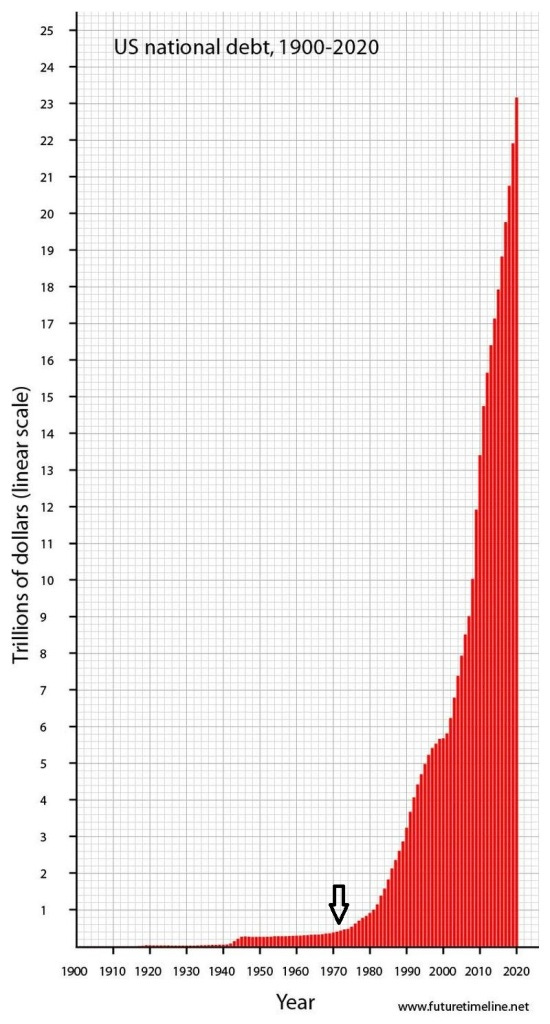

Based on the economic science of the 1930s, there was every reason to believe that the Chicago Plan could have and would have worked. Tragically for the United States (but quite profitably for the financial interests which controlled our economy), the Chicago Plan was ignored. The privately-owned Federal Reserve remained in control of the issuance of new fiat money, and the privately-owned commercial banks continued to create new debt money by fractional lending. For a few decades, the flaws of this system were kept in check by the discipline of the gold standard, but when the U.S. dollar lost its redeemability in gold in 1971, economic catastrophe ensued — a catastrophe evidenced across our country, in the financialization and deindustrialization that has ended the American Dream.

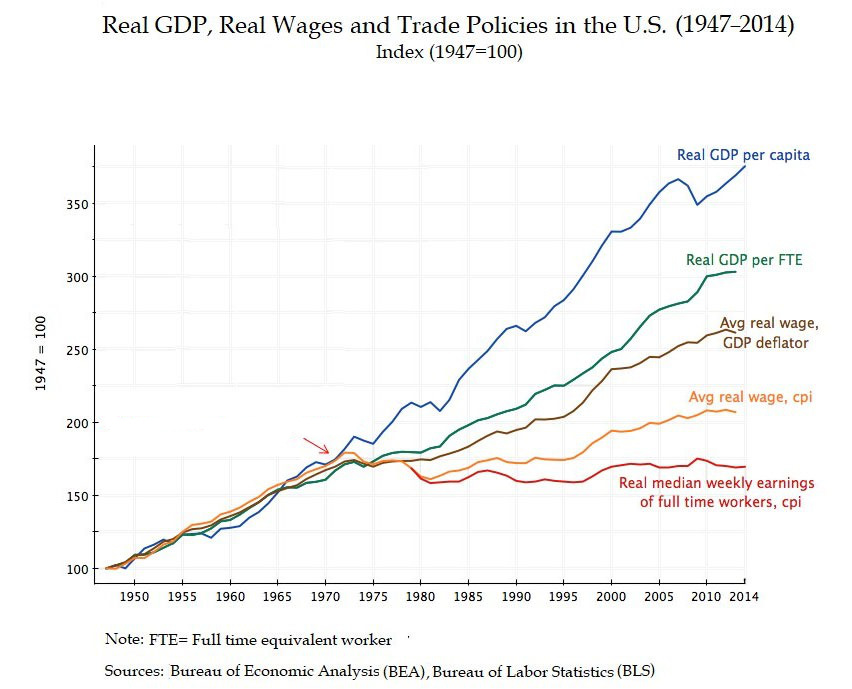

I have elsewhere linked the website WTF Happened in 1971, a compilation of charts and tables demonstrating the pernicious effects of the petrodollar system. But some of them bear reviewing again:

Just as the Great Depression had made it possible for heterodox economics to flourish, so too did the Great Recession of 2008 make it briefly possible for economists to again discuss heterodox approaches to monetary economics. In August 2012, a a pair of economists named Jaromir Benes and Michael Kumhof of the IMF did just that when they released a paper titled the Chicago Plan Revisited. Like Simons and Fisher before them, Benes and Kumhof argued that the US economy should move to full-reserve banking with government-created money rather than debt money.

Unfortunately, just as Simons and Fisher’s Chicago Plan was ignored by policy makers in the 1930s and 1940s, Benes and Kumhof’s Chicago Plan Revisited was ignored by policy makers in the 2010s and 2020s. Instead, our neoliberal leaders simply “kicked the can down the road.” The United States considered to borrow money from private banks, continued to expand its national debt, continued to continued to enrich its rentier class, continued to impoverish its workers, continued to deindustrialize its economy.

Now it is 2023 and, as I noted in The System is Down, “the Petrodollar System that has served as the bedrock of world finance since the 1970s is over.” Subsequent events since that article was written have only continued to prove me correct: The world is de-dollarizing. With de-dollarization at hand, we are approaching a new crisis — and, because it will bring about the end the dollar’s utility as a reserve currency — this crisis will be one that makes 2008 seem like a momentary downturn. The chaos and turbulence ahead can and must be leveraged to reform the system. This time, this crisis, we must succeed in ending the Fed, because the alternative is the end of America in everything but name — the end of America as a First World country with a middle class.

In the words of Ron Paul, to save America we must end the fed. But what do we replace the Federal Reserve System with? The system of the Chicago Plan.

Principles of the Chicago Plan

According to Benes and Kumhof, the Chicago Plan is based on two simple principles:

Full Reserve Banking: All demand deposits must be be 100% backed by government-created money. This principal puts an end to fractional-reserve backing.

Prohibition on Credit Money Creation: All new bank credit is financed either through retained earnings as government-issued money or by borrowing pre-existing government money from non-banking entities. This principle prohibits banks from conjuring new deposits out of nothing.

This seems straightforward enough. But what do Benes and Kumhof mean by “government-issued money”? Are they advocating for the return of a gold-backed commodity money as we had prior to debt money? No, not at all — in fact, it would be impossible to implement the Chicago Plan with redeemable commodity money.

In the context of the Chicago Plan, “government-issued money” refers to irredeemable bank notes issued by the US Treasury directly (e.g. without doing so through a central bank), much the same as Abraham Lincoln’s greenbacks. Benes and Kumhof explain:

[I]t is critical to realize that [under the Chicago Plan] the stock of reserves, or money, newly issued by the government is not a debt of the government. The reason is that fiat money is not redeemable, in that holders of money cannot claim repayment in something other than money. Money is therefore properly treated as government equity rather than government debt, which is exactly how treasury coin is currently treated under U.S. accounting conventions (Federal Accounting Standards Advisory Board (2012)).

The concept of “money as equity” is relatively new in monetary economics. The two prevailing theories of money are the “commodity money” and “credit money” schools. In the former, money is a token that can be redeemed for a commodity of value. In the latter, money is an entry on a ledger of credit and debt.

Economists Biagio Bossone and Massimo Costa of the World Bank explain money as equity in their article The Accounting View of Money: Money as Equity, where they write:

Legal tender money is neither “credit” for its holders nor “debt” for its issuers. It is instead net wealth of the holders and net worth (equity) of the issuers. Money accounted as the issuer’s equity implies ownership rights. These rights do not give money holders possession over the entity issuing the money (as shares giving investors ownership of a company or residual claims on the company’s net assets). Rather, they consist of claims on shares of national wealth, which money holders may exercise at any time. Those who receive money acquire purchasing power on national wealth, and those issuing money get in exchange a form of gross income that is equal to its nominal value. The income calculated as the difference between the gross revenue from money issuance and the cost of producing money is known as “seigniorage” and is appropriated by those who hold (or are granted) the power to issue money.

Because it relies on equity money, the Chicago Plan represents a sort of “third way” between commodity money and debt money.

Implementation of the Chicago Plan

The implementation of the Chicago Plan is a two-stage process which, if properly executed, maintains the money supply and causes neither hyperinflation nor debt deflation.

Prior to the Chicago Plan: When the Chicago Plan begins, the balance sheet of the banking system (in aggregate) looks like this:

On the left side of the balance sheet are the banks’ assets — government bonds, short-term loans, mortgage loans, and investment loans. On the right side of the balance sheet are the banks’ liabilities and equity. As in real life, the banking system has negligible cash assets - for our purposes, not even visible on the sheet. The demand deposits from customers have essentially no reserve behind them - the system is hugely leveraged and susceptible to bank failure at any time. (This is not hyperbole - The Federal Reserve set the reserve ratio at 0% in 2020.)

Chicago Plan Stage 1: In the first stage of the Chicago Plan, all banks are required to borrow money from the US Treasury sufficient to equal their assets. This adds an asset to the banks’ balance sheet (a money reserve) as well as a liability (credited to the US Treasury).

Where did the US Treasury get the money it loaned? Itself: The US Treasury simply created the money, at no cost to itself.

Chicago Plan Stage 2: In the second stage of the Chicago Plan, the US Treasury cancels all government bonds on the banks’ balance sheets. This eliminates the “government bonds” asset and shrinks the “treasury credit” liability. It then transfers part of the remaining treasury credit (which is an asset of the Treasury) to American households and businesses by way of restricted accounts that must be used to repay outstanding bank loans. This eliminates the banks’ “short-term and mortgage loan” assets and further shrinks the “treasury credit” liability. That leaves only investment loans outstanding, with money unchanged and bank debt (treasury credit) much reduced. The new balance sheet of the banking system has a double-thick line between reserves/deposits and loans/credit + equity. This represents the fact that full-reserve banks cannot lend out their cash against deposits.

Following stage 2 of the Chicago Plan, the United States has a full-reserve banking system in place, with interest-free equity money issued by the Treasury directly. As a result of the issuance of equity money, government and consumer debt is vastly reduced (to a level almost equivalent to a debt jubilee) but inflation does not occur because for every excess dollar of equity money created, a dollar of debt money was destroyed or removed from circulation.

This is a much simplified explanation of the plan; economists who seek a fuller explanation of the implementation of the Chicago Plan are referred to the paper Chicago Plan Revisited.

Benefits of the Chicago Plan

The Chicago Plan has six major benefits:

Regulation of Credit Cycle: By stopping banks from generating their funds in credit surges and then vanishing them during subsequent downturns, credit cycles — seen as the main drivers of business cycle ups and downs — could be more effectively regulated. Austrian economists everywhere rejoice!

Elimination of Bank Runs: The 100% reserve stipulation would put an end to bank runs. Demand deposits would be retained dollar-for-dollar. Even if 100% of its customers simultaneously demanded the return of their deposits, the bank would remain solvent. The FDIC can be shut down.

Decrease in Government Interest Cost: By permitting the government to directly release money without interest rather than borrowing it from banks with interest, the government's interest costs would decrease substantially, leading to a significant cut in net government debt since non-repayable government money is an asset to the public, not a liability. The US National Debt is largely eliminated and interest payments on the National Debt never destroy us.

Decrease in Public and Private Debt: As the act of creating money would no longer demand the parallel creation of bank debts, there would be a notable drop in both public and private debt levels. When productivity increases, new money can be added to the system by government spending; alternatively, government spending can be used for productivity increasing infrastructure — in both cases without debt.

Increase in Long-Term Output: Reforming the monetary system leads to an increase in the country’s output. When debt levels decrease, real interest rates also decrease. Tax rates can be reduced because the government can rely on seigniorage income and does not have to pay interest on the national debt.

No Steady-State Inflation: By separating the money function from the credit function, the Chicago Plan can eliminate the persistent inflation that characterizes our economy. When the economy grows, new money can be created without creating debt that requires yet more money to be created to pay.

Points 5 and 6 can be a bit hard to grasp. Here’s a model that might help. Imagine a simple economy with 10,000 units of goods and $100,000 in currency, such that on average each unit of goods costs $10. Imagine that, through improvements in the division of labor, the economy beings to produce 11,000 units of goods. What happens?

Under a hypothetical fixed money system, deflation would result. The average cost of each unit of goods would drop to $9.09. Deflation has many pernicious economic consequences and is generally considered undesirable. Nobody wants this outcome.

Under our current debt money system, the banking system would loan an additional $10,000 of currency to businesses and consumers. This would maintain stable prices — temporarily. Unfortunately, because it was created by lending, the additional $10,000 of currency would carry with it interest that would have to be paid back. And how can this interest be paid? If it is siphoned out of the productive economy and returned to the banks, then the money is destroyed and we create debt deflation — and that cannot be allowed to occur. Therefore, the banks must lend (create) even more money into circulation so that sufficient money exists to pay the interest on the last round of money creation. This cycle continues, ad infinitum, with debt exponentially increasing, just as the images from WTF Happened in 1971 show.

Under the proposed equity money system, the government would create an additional $10,000 of currency and use that to buy the extra 1,000 goods. Printing this money would generate $10,000 of income for the government — which therefore can charge lower taxes. The additional $10,000 in circulating currency would maintain price levels at $10 per unit of goods. And no debt would be created — full stop.

Criticism of the Chicago Plan

The Chicago Plan has, of course, come under sharp criticism by the banking system, which has a vested interest in maintaining its position as economic rentier par excellence. There are two main criticisms, one from proponents of commodity money and one from proponents of debt money.

Debt money proponents, who are largely orthodox neoclassical economists employed by the banking system, do not like that the Chicago Plan exploits government-issue fiat money. These proponents will shamelessly assert that giving government control over the money supply is certain to bring about rampant inflation and that only wisely-managed private banks can be trusted to maintain a stable money supply — all while ignoring the fact that by far the greatest inflation of all time has occurred under debt money. Their shamelessness is matched only by their greed for the economic rent accruing to those who hold the power of issuing debt money. Economist Michael Hudson has spoken much on this.

Commodity money proponents do not like the fact that the Chicago Plan depends on government-issue fiat money. They believe that governments are always and everywhere irresponsible with money, and that enabling the government to print money will cause hyperinflation. Therefore, the world must revert to commodity money. I am very sympathetic to this view, and personally maintain a large proportion of my meager wealth in gold and silver. However, commodity money theorists have not (to my knowledge) offered a substantive plan for how to extricate American from its current plight and get to their ideal system — and there might not be one. In my judgment, if a commodity money system is desired, the Chicago Plan should still be pursued, because converting to commodity money system would be much easier once the 100% full-reserve system was in place and the debt stranglehold released.

The Chicago Plan is the Physiocratic Plan

The adoption of the Chicago Plan is the first plank in the Physiocratic platform. It addresses the manifold concerns I have brought up in my earlier writings and offers hope (a rare thing here at the Tree) for our economic recovery. When the next crisis comes, I pray that you will join me in bringing an end to the disastrous Federal Reserve System and poisonous petrodollar and embrace debt-free equity money with full-reserve banks.

I have not yet finished reading all the papers (regarding the Chicago plan) linked up; but so far it passes the "Smell Test" and looks quite viable. I will come back on this comment (upon finishing everything in full) and opine on it more thoroughly.

The final point made (re: moving to Commodity Money from Equity Money being easier) is Correct as per Professor Michael Hudson's research (Historical & Economic) on various Human societies these past few millenia and the manner in which they organized Exchange in general:

Namely, the adoption of Gold &/or Silver has always been preceded by a "transitionary" period in which the King/Chieftain, etc decreed (by force of course) that *insert object here* has intrinsic value and is henceforth going to be doled out by the "state".

Fascinating! You need to get together with Alexandria Ocasio Cortez with this. You have described a synthesis of Austrian Economics and Modern Monetary Theory! Talk about a creative coalition!

This Chicago Plan looks like a very interesting way to pull off a jubilee, but that Chicago Plan 2 diagram bothers me. It has banks limited to lending treasury credit and equity. Why would a bank ever bother with deposits? Can checking fees justify the effort? And what of new banks? Where do they get money to lend?

A bank *can* make loans using deposits without maturity transformation iff the loan maturities match the deposit maturities. That is, lending demand deposits is a definite no-no. You have to put money in a CD in order to earn interest.

Financing mortgages gets tricky. Who is going to put money into a 30 year CD? One solution is to continue letting FANNIE MAE and FREDDIE MAC do the actual financing. Another possibility would be for banks to offer Individual Retirement Accounts and use the locked funds to finance mortgages.

Yet another possibility would be to break mortgages into time based tranches, as described here:

https://conntects.net/blogPosts/GreenandFree/68