The Case for Pagan Monotheism

Was there Widespread Worship of a Monotheistic God by Pagans in Late Antiquity?

Over the last 25 years, a quiet war has been fought. The warriors are professors of ancient history, classical studies, comparative religion, and theology. Their frenzied yet multisyllabic war-cries and footnoted berserker furies echo through the pages of Brill’s Plutarch Studies, the Oxford University Press, and other battlefields. It is a war fought for the very soul of Late Antiquity itself.

The war began with the publication of Polymnia Athanassiadi and Michael Frede’s book Pagan Monotheism in Late Antiquity in 1999. The war escalated with the publication of Frede’s 2010 follow up, One God: Pagan Monotheism in the Roman Empire. It continues even now.

Peter Lötscher, in an essay entitled “Plutarch’s Monotheism and the God of Mathematics” published in the book Plutarch’s Religious Landscapes (2021), summarizes the state of the ongoing conflict:

In recent decades there has been a debate about the spread and value of monotheism in antiquity, which continues to this day. According to a traditional view of history of religion that was shaped in late antiquity, Christianity has replaced a polytheistic and untruthful religious system with an enlightened monotheism. This picture of progress towards monotheism has been discussed anew [as] scholars have questioned whether Christianity had brought anything new in relation to the oneness of God…

Frede argued that already the “pagan philosophers, in particular the Platonists, were monotheists in precisely the sense the Christians were”. Following… Frede’s publications, a fierce discussion about pagan monotheism commenced.

How influential has this work been? Before Frede’s Pagan Monotheism in Late Antiquity was published, the very idea of pagan monotheism was deemed an oxymoron, a self-contradiction. Today, Frede and his allies are winning the war. M.J. Edwards, reviewing the debate in The Journal of Theological Studies, regretfully admitted:

Is there an air of triumph among the classicists? Forced for two millennia to admit the singularity, if not the singular truth, of Christianity, they have at last exposed [as false] its claim to have been the one religion of antiquity, apart from Judaism, which maintained the existence of a single god.

If Frede is right, then Christianity and Judaism are not the sole monotheistic religions of antiquity. There was another branch in the tree, an Hellenic branch that grew from the fertile soil of Greco-Roman philosophy and myth. A forgotten tree, perhaps, but one with deep roots.

Who were these practitioners of a now-forgotten faith, what did they believe, and in what manner did they worship? Surprisingly, we can answers to all of these questions, largely due to a series of incredible archeological findings throughout Macedonia, Anatolia, Cyprus, and other Mediterranean lands.

But before we delve into the actual beliefs of the pagan monotheists, we need to meet the two main objections raised by those who deny the thesis itself.

Objection #1: Pagan Monotheism Isn’t Really Monotheism

The first line of attack on pagan monotheism is to assert that pagan monotheism isn’t really monotheism because it’s actually “monolatrism” or “megatheism” or “quasi-monotheism” or “monism.” To assess whether that’s true, we must ask: What is monotheism?

As it turns out, the definition of monotheism is actually quite contentious. Is Christianity monotheistic given the existence of the Trinity? All Christians say it is, but many Muslims say it’s not. Is Zoroastrianism monotheistic given the existence of Ahriman? The Zoroastrians say it is, but many Christians and Muslims say it’s not. It goes on and on.

I believe the best definition of monotheism is that presented in Michael Frede’s essay “The Case for Pagan Monotheism in Greek and Graeco-Roman Antiquity” in One God. There Frede writes:

We take a monotheist to be a person who not only believes in one god, but a god conceived in such a way that there is no space for other gods… [while] a polytheist is a person who not only believes in many gods, but also in no gods conceived of in such a way as to be a monotheistic god.

[But] there is something problematic about saying that a monotheist believes in one god, whereas a polytheist believes in many gods. For this obscures the fact that their conceptions of a god, and to that extent the meaning of the word ‘god’ are not quite the same. A polytheistic god is not a god in quite the same way and sense in which a monotheistic god is.

This, in principle, opens up the possibility for a monotheist to say that, strictly speaking, there is just one god, namely God, but that there are also beings which, given the way the word ‘god’ is commonly used, would be called ‘gods.’ Thus in principle a monotheist could talk of many gods without thereby in the least compromising his monotheism, since the many gods would not be gods in quite the same sense as God.

A monotheist, then, must believe there is only one God, but can accept the existence of other small-g gods.

Why do I consider this the best definition? Well, Frede’s definition of monotheism has two strong virtues. The first virtue is that it is even-handed: it is not polemically skewed. It affords Judaism and Christianity the same equal protection which it affords pagan monotheism — and the Abrahamic religions do need that defense! After all, the Abrahamic religions have no shortage of sons of God, archangels, angels, demons, and other immortal beings of the heavenly host, and no shortage of critics who assert that the existence of those beings makes the religion polytheistic.

For instance, consider Psalm 82:

God standeth in the congregation of the mighty; he judgeth among the gods... I have said, Ye [are] gods; and all of you [are] children of the most High.

In Hebrew, both “God” and “gods” are written as elohim. Marti Steussy, in the Chalice Introduction to the Old Testament, explains “In the first verse of Psalm 82… elohim has a singular verb and clearly refers to God. But in verse 6 of the Psalm, God says to other members of the council, ‘You [plural] are elohim. Here elohim has to mean gods.” God is talking to other gods!

Psalm 82 is not an anomaly. Many other similar usages litter the pages of the Old Testament. Today the notion that God presides over a divine council consisting of small-g gods has wide support among leading Biblical scholars. But does this mean Judaism or Christianity are not monotheistic? Certainly not under Frede’s definition, for both Judaism and Christianity believe in only one God, whatever else they might believe about small-g gods. Sidestepping those debates creates a “big tent” for discussion.

The second virtue of Frede’s definition of monotheism is that it allows us to distinguish between monolatrists (who worship just one god or God) and polylatrists (who worship many gods), and between polytheists (who believe in many gods but do not believe in one God) and monotheists (who believe in one God but may or may not believe in many gods).

This division or formulation makes possible to understand that pagan monotheism is actually a sub-type of monotheism called polylatric monotheism — a religion which admits the existence and even the praiseworthiness of many gods while believing in and worshipping only one God.1

Objection #2: Pagan Monotheism Isn’t Really Pagan

The second objection to pagan monotheism is that it isn’t really pagan. This line of attack is more complex. It proceeds as follows:

The term paganism was coined by the Christians of Late Antiquity to refers to all other religions save their own and Judaism.

Therefore, a religious tradition that derives from Judaic or Christian roots is not truly pagan.

Therefore, if we we can show that Judaic or Christian influence was at the root of pagan monotheism, then we must accept that it is just an offshoot of Abrahamic religion. Rather than a different branch in the tree, it is merely a grafted limb.

We can, in fact, show that Judaic or Christian influence was at the root of pagan monotheism by demonstrating that pagan monotheists were actually just theosebeis or “God-fearers,” that is, Hellenes who worshipped the Jewish god.

Or so the critics of Frede’s thesis claim. A number of scholars have answered this objection in various ways. Among them are the aforementioned Michael Frede; George H. van Kooten; Peter Lötscher, and finally Stephen Mitchell, Frede’s co-author and co-editor in One God. Let’s review them.

Frede’s Answer

Michael Frede answers the objection by asserting that the origin of pagan monotheism was from Hellenistic philosophy, not Jewish religious practice. In his essay “Monotheism and Pagan Philosophy in Late Antiquity,” in Pagan Monotheism, Frede writes:

[A]s far as the question whether there is one God or whether there are many gods is concerned, it is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to distinguish between the Christian position and the position of Plato, Aristotle, Zeno, and their followers and thus the vast majority of philosophers in Late Antiquity.

[T]he Platonists, the Peripatetics, and the Stoics do not just believe in one highest god, they believe in something which they must take to be unique even as a god. For they call it “God” or even “the God",” as if in some crucial way it was the only thing which deserved to be called god. If, thus, they also believe that there are further beings which can be called “divine” or “god",” they must have thought that these further beings could be called “divine” only in some less strict, diminished, or derived sense. [Likewise], the Christians themselves speak not only of the one true God, but also of a plurality of beings which can be called “divine” or “god”; for instance, the un-fallen angels or redeemed and saved human beings.

In other words, if one applies Frede’s definition of monotheism to the views of the ancient philosophers, then the ancient philosophers must be deemed as monotheistic as Christians. And since the beliefs of those philosophers were formed before the translation of the Old Testament into Greek and before the Jewish diaspora carried Jewish thought throughout the Roman Empire, their beliefs would be a form of indigenous monotheism.

However, Frede’s essay alone does not carry the day. Many scholars might be willing to admit that the pagan philosophers were monotheists while denying that any pagan religion was or became monotheistic until it encountered Judaism or Christianity.

Van Kooten’s Answer

George H. van Kooten answers the objection that pagan monotheism isn’t really pagan by positing that Roman religion was originally monotheistic!2 In his article “Pagan and Jewish Monotheism According to Varro, Plutarch, and St. Paul: The Aniconic Monotheistic Beginnings of Rome’s Pagan Cult,” van Kooten cites the writings of a number of ancient thinkers, including St. Paul, Varro, Strabo, and Plutarch, to make his point.

Because Plutarch enjoys most-favored philosopher status here at Tree of Woe, we will focus our attention there. In his Life of Numa, Plutarch asserted that the ancient Roman king Numa, the successor of Romulus, was an aniconic monotheist. He writes:

[Numa’s] ordinances concerning images are altogether in harmony with the doctrines of Pythagoras. For the philosopher maintained that the first principle of being was beyond sense or feeling, was invisible and uncreated, and discernible only by the mind. And in like manner, Numa forbade the Romans to revere an image of God which had the form of man or beast. Nor was there among them in this earlier time any painted or graven likeness of Deity, but while for the first hundred and seventy years they were continually building temples and establishing sacred shrines, they made no statues in bodily form, convinced that it was impossible to apprehend Deity except by the intellect.

If Plutarch, and by extension van Kooten, are correct, then pagan monotheism has very deep roots indeed, dating back to the founding of Rome.

Lötscher’s Answer

Peter Lötscher also answers the objection by turning to Plutarch. In his essay “Plutarch’s Monotheism and the God of Mathematics,” Lötscher writes:

Plutarch is perhaps one of the most interesting authors for the current discussion on the existence of pagan monotheism [because of] the important role Plutarch plays in discussions about a pagan theology. As a priest at the Oracle of Delphi and as a Platonist philosopher, our author combined traditional cult and philosophical thought. Plutarch’s testimony, consequently, is especially interesting for the connection he established between a coherent theology and the lived religion of his time.

When we speak of Plutarch as a monotheist, we do not mean to equate his image of God with the Christian notion. Rather I assume that in antiquity there existed several types of monotheism. R. Hirsch-Luipold, for instance, has suggested to distinguish between the belief in one sole God which should be called “monotheism” and the worship of only one God which should be called “monolatry”. He describes Plutarch’s concept of God as “polylatric monotheism.”

Plutarch was a monotheist, but not in the Christian sense. The oneness of God or the Divine plays a highly prominent role in his work. In a Pythagorean sense Plutarch spoke of the God of mathematics as the Μονάς (‘monad’). He was able to integrate these Pythagorean thoughts into a Platonic image of God. One of the differences between Christian monotheism and Plutarch’s monotheism is the inclusiveness of Plutarch’s monotheism. Plutarch would never have demanded the elimination of traditional gods of various peoples. Regarding this point, his monotheism has to be distinguished from a Christian form of monotheism in Antiquity, which identifies the Gods of the nations with evil spirits. That Plutarch was quoted by numerous Greek apologists, however, may indicate that thoughts found in his writings were also interesting for Christianity.

So, in Lötscher’s view, the writings of Plutarch reveal that at least some of the philosophers and priests in Late Antiquity were alike in believing in a form of monotheism. It was not the case that the philosophers believed one thing and the priests another; the philosophers were also the priests, and they were monotheists. Polylatric monotheism is the real religion of the ancients.

Mitchell’s Answer

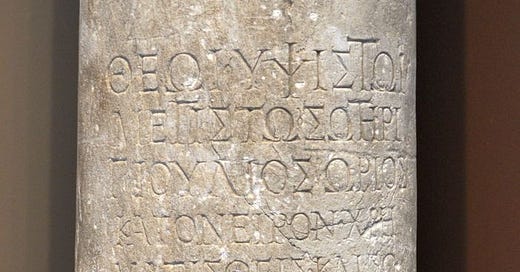

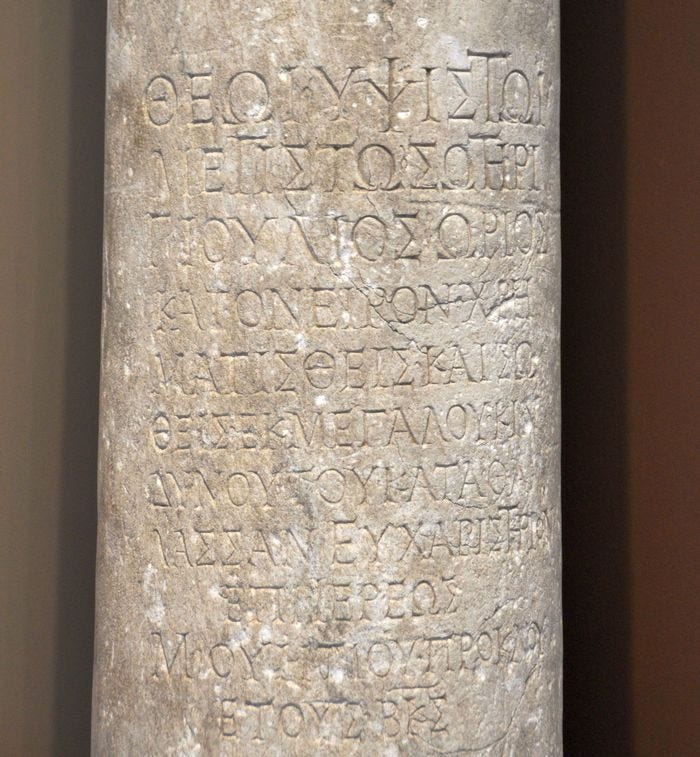

Stephen Mitchell’s answer to the objection that pagan monotheism isn’t really pagan entails a review of the archeological evidence for the worship of Theos Hypsistos (sometimes also called Zeus Hypsistos). His article “The Cult of Theos Hypsistos between Pagans, Jews, and Christians,” in Pagan Monotheism in Late Antiquity, analyzed all known inscriptions to Theos Hypsistos — 293 in total as of 1999. His follow-up article, “Further Thoughts on the Cult of Theos Hypsistos,” in One God, written 11 years later, broadened the inquiry to 375 inscriptions.

Based on the archeological findings he documents, the cult of Theos Hypsistos must be considered one of the most well-attested and popular cults in all of Antiquity!

Why does that matter? What do inscriptions to Theos Hypsistos have to do with pagan monotheism? Quite a lot: Theos Hypsistos is Ancient Greek for “God Most High,” and the archeological evidence for the cult of Theos Hypsistos represents the strongest evidence ever compiled for pagan monotheism. Surviving inscriptions amply demonstrate that the worshippers of God Most High saw him as a monotheistic God who sat above and superior to the small-g gods (who were deemed merely his “angels”) and created him with supreme power, goodness, and perfection.

But now comes the plot twist: As it happens, Theos Hypsistos was also the Greek term used to translate the Hebrew term El Elyon - both literally mean “God Most High.” As a translation for El Elyon, Theos Hypsistos appears over 110 times in the Septuagint and is used throughout the Jewish Pseudepigrapha. On this basis, traditional scholars (e.g. those in the anti-Frede camp) have asserted that the worshippers of Theos Hypsistos were actually just worshippers of the Jewish God who did so in a Hellenistic manner. They were thus either Hellenized Jews or were the non-Jewish worshippers of El Elyon, the aforementioned theosebeis or “God-fearers” from earlier.

After reviewing all of the epigraphic evidence, Mitchell concludes that it is highly unlikely that Judaism was the real or exclusive basis for worship of Theos Hypsistos:

It is, perhaps, a formal possibility that… [the Jews of the Diaspora] could have spread and implanted the entire basis of the cult in local populations which they encountered. On this interpretation, Jewish belief would have formed the basis for all Hypsistarian worship.

But this reconstruction is historically and sociologically highly implausible. The cult of Zeus Hypsistos in Greece and Macedonia surely developed from local roots… The concept of the a highest god and his angels is likely to have evolved independently in the unhellenized communities of the interior of Asia Minor and on the north shore of the Black Sea. In the first case it drew on an indigenous tradition which favored both monotheism and ascetic religious morality; in the second it may owe something to abstract Iranian ideas of divinity.

The Case for Pagan Monotheism

The case for pagan monotheism can thus be summarized as follows:

Monotheism rightly defined differentiates between the God and the gods. It insists on the existence of the God, but can incorporate the existence of many small-g gods as emissaries, emanations, or servants of the God. To verbally differentiate the God (Theos) from a god (theos), the God is often called God Most High (Theos Hypsistos).

Virtually all of the pagan philosophers of antiquity, including the Platonists, Peripatetics, and Stoics, were monotheists who believed in God Most High. Even those philosophers who were priests of the pagan gods (as Plutarch was a priest of Apollo at Delphi) believed that the pagan deities were small-g gods subordinate to and governed by God Most High. The God/god distinction was, in their mind, the correct understanding of pagan religious belief.

Far from being limited to the philosophers, the practice of worshipping a monotheistic God was widespread among the population of Late Antiquity. The Cult of God Most High was among the more popular in the Roman Empire, with abundant evidence for worship throughout Greece, Macedonia, the Black Sea, and Anatolia.

The geography and chronology of the archeological evidence for the Cult of God Most High makes it highly implausible that Jewish belief would have formed the primary basis for it. Worship of Hypsistos was indigenous to Greece, Macedonia, Asia Minor, and the Black Sea region, possibly drawing on Iranian rather than Abrahamic theology. At least some of Antiquity’s scholars believed that Roman religion was itself monotheistic in its origin.

In our next Contemplations, we will explore the practices of the Cult of Theos Hypsistos to see if its iconography, prayers, and rituals can be reconstructed from the available archeological and textual evidence.3

An interesting, but tangential, question is whether Christianity itself qualifies as polylatric monotheism. Jews and Muslims have been known to assert that Christianity is not really monotheistic because of the existence of the Trinity, and Protestants have been known to assert that Catholicism is not really monotheistic because of the veneration of the Virgin Mother, the saints, and the angels. Under the Frede definition, however, Christianity is inarguably monotheistic, with certain denominations possibly being polylatric monotheism and others being monolatric monotheism.

This thesis is pursued on a worldwide basis by Winfried Corduan in the book In the Beginning, God, which makes the case for monotheism as the original religion of all of humanity. If you believe the case for original monotheism, then the case for an indigenous monotheism in Antiquity is much easier to believe, obviously.

I contemplated adding a section to this essay explaining why I believe this to be a topic with important implications for our wider cultural struggle, and not just a historical or theological curiosity. In the interest of brevity, I have opted to allow the implications speak for themselves.

"A Monotheist is one whose conception of *God* is such that there can be Only One Supreme Being".

Correct. Relevant:

https://renovatio.zaytuna.edu/article/everything-other-than-god-is-unreal

In general, every Muslim theologian (who has seriously studied the religion) would agree with you.

That Monotheism was the default, starting state of Humanity; on that you would also find agreement.

The blessed Prophet (Peace Be Upon Him) notes in the Hadith that 124,000 Prophets (of which 313 were Messengers) have been sent to every nation of Mankind. Therefore *at the minimum* there are 124,000 Prophets (not counting the ones sent to Djinn, as well as Saints and whatnot who are 'lower' relative to the Prophets & Messengers with regard to righteousness).

So assuming 117 billion Humans "have ever existed" (I don't entirely trust this number, but let's run with it for now) and trillions of Djinn have been around also, it makes sense.

In fact; French & German Anthropological schools back in the early 20th century derided the "Mohammedans" for this age-old view. You can find several such essays (from the 1910s & 1920s) which speak about the "peculiar Mohammedan view that Monotheism came PRIOR to Animism".

This was back when they were trying to promulgate the "Animism -> Spiritism -> Polytheism -> Monotheism -> Atheism" storyline in Academia (which they succeeded in promoting).

It's good to see that this Drivel is finally being swept into the Dustbin of history, where it correctly belongs!

Well, this takes me back to watching Dr. Gene Scott lecture on the Lost Tribes and other ancient historical mysteries. He was reading some book which claimed that some of the wealthier Hebrews escaped Egypt by ship as the Hebrews in general lost favor with the Pharoah -- much as American billionaires have homes in places like New Zealand in case things go south here.

In particular, note the story of Judah's twin sons by Tamar in Genesis 38. Zerah's hand came out and the midwife tied a thread to his hand -- which then went back in and Perez, the ancestor of the kings of Judah, came out first. Do recall that Jacob split the blessings of Abraham, giving the blessing of great numbers to Joseph's sons, and the kingship to Judah's descendants.

The descendants of Zerah -- Judah's true firstborn by Tamar -- disappear from the narrative. The book Dr. Gene was reading claimed that the descendants of Zerah founded Troy. And when Troy was sacked, they founded Rome.

Your mention of the early Roman king being a monotheist brings this memory back.

And then there is this: the chief god of the Roman pantheon was sometimes called Jove. Pronounce the J and V as one should in Latin. The name seems mighty close to the proper name of God in the Old Testament...