The Physiocratic Platform: Taxation

Because there's Really Only Two Types of Woe, Death and Taxes

Back in October 2021 (three years ago!) I introduced the label Physiocracy to describe my own political views, situated somewhere between Paleolibertarianism, National Capitalism, and Georgism.

In November 2022, I drafted an initial Physiocratic Platform of structural reforms for the United States. I paid no mind to whether this platform could be implemented today — nothing meaningful can be implemented today, because the American system is broken, and no one can stand to think about how to fix it. As such, the platform was not presented as an exercise of “the art of the possible” but as an overview of the necessary. At the time, I noted:

Many of the items in this list are complex enough to merit white papers or even books. In particular, the reform of the Federal Reserve and implementation of the Chicago Plan, the instatement of a land tax, and other measures merit much deeper discussion.

In September 2023, I wrote a follow-up article entitled The Physiocratic Platform: Banking, where I delved into the Chicago Plan to replace the Federal Reserve system with full-reserve banking using debt-free money.

It’s been a year since then, and since I’m apparently developing Physiocracy at the leisurely pace of one topic per year, that means it’s time to flesh out another aspect of the agenda. Today I want to discuss taxation.

Setting the Baseline

Before we propose tax reform, we need to understand the current taxation regime. If you’re already deeply familiar with this material, please feel free to skip ahead to the next section. If not, read on for lots of woe!

As of 2024, the U.S. GDP stands at $26.7 trillion. The total budget for all U.S. governments, including federal, state, and local, is $10.5 trillion - a staggering 40% of our total GDP. That money has to come from somewhere, and the majority of it comes from taxes.1

The government spending can be further broken down into approximately $5.08 trillion for the federal government (20% of GDP); $3.59 trillion for state governments (13%); and $1.83 trillion for local governments (7%). Each of these tiers of government has its own distinct system of taxation. Let’s review them.

Federal Taxes

At present, the federal government funds itself with the following:

Individual Income Tax: The largest source of federal revenue (50%), this tax is levied on the income of individuals, including wages, salaries, dividends, and capital gains. This is a progressive tax.

Payroll Taxes: The second largest source (36%), payroll taxes include the Social Security Tax, Medicare Tax, and Federal Unemployment Tax (FUTA).

Corporate Income Tax: A tax on the profits of corporations.

Excise Tax: Taxes on specific goods and services, including: alcohol, tobacco, fuel, airfare, firearms, ammunition, medical devices, and health insurance.

Estate Tax: Imposed on the transfer of a deceased person’s estate, above a certain exemption limit.

Gift Tax: Taxed on the transfer of money or property while the giver is alive if it exceeds certain thresholds.

Customs Duties: Taxes on goods imported into the United States, used to regulate trade and generate revenue.

Capital Gains Tax: Taxes on the profits from the sale of investments, like stocks, bonds, or real estate.

Additional Medicare Tax: An additional 0.9% on higher-income earners.

Net Investment Income Tax: A 3.8% tax on investment income for high-income earners.

How important are each of these? As noted above, the individual income tax is by far the largest source of revenue, accounting for about 50% of all federal revenues. Payroll taxes account for about 36% of federal revenue. Corporate income taxes account for 8% of federal revenue. Excise taxes account for 3%, customs duties 1%, and estate and gift taxes 1%. In total, the federal government takes in $3.22 trillion in taxes.

But the government spends $5.08 trillion! The federal government pays for the $1.86 trillion deficit by issuing debt, primarily Treasury bonds. About 20% of this debt is monetized, that is, bought by the Federal Reserve in exchange for newly-issued Federal Reserve notes. Our tax system should be designed such that the U.S. is not laden with ever-increasing debt.

State and Local Taxes

The various state and local governments fund themselves with a separate set of taxes. While most states have individual income tax, corporate income tax, and excise taxes, the majority of their revenues come from other taxes the federal government doesn’t impose.

Individual Income Tax: Most states levy income taxes on individuals, although rates and brackets vary. A few states, such as Florida and Texas, have no state income tax.

Corporate Income Tax: Taxes on the profits earned by businesses operating within the state. Not all states impose this tax.

Excise) Taxes: These are imposed on specific goods such as alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, telecom, and utilities.

General Sales Tax: A tax on the sale of goods and services, which is usually a percentage of the sale price. Some states do not have a general sales tax (e.g., Oregon, New Hampshire).

Use Tax: Complementary to sales tax, this applies to goods purchased out of state but used within the state.

Real Property Tax: Levied on the value of land and buildings owned by individuals or businesses.

Real Estate Transfer Tax: Levied when property is sold, based on the value of the transaction.

Documentary Stamp Tax: Imposed on legal documents such as deeds and mortgages.

Personal Property Tax: Some states tax personal property like cars, boats, and machinery, particularly for businesses.

Estate Tax: Some states impose taxes on the transfer of estates after death, separate from the federal estate tax.

Inheritance Tax: A tax on the beneficiaries who inherit money or property, imposed in a few states like Iowa and Kentucky. This is distinct from an estate tax, which is paid by the deceased’s estate.

Motor Vehicle Registration Fees: Annual fees for registering vehicles, which vary based on the type of vehicle, weight, and age.

Gross Receipts Taxes: Some states, such as Ohio and Nevada, impose taxes on a business’s gross receipts, as opposed to net profits.

Business Franchise Taxes: Imposed on businesses for the privilege of doing business in the state, based on net worth or capital.

Severance Taxes: Taxes on the extraction of natural resources such as oil, gas, and minerals. States like Texas and Alaska rely heavily on severance taxes for revenue.

Transient Occupancy Taxes: These are levied on hotel stays, typically to fund tourism and local services.

Insurance Premium Taxes: Taxes on insurance companies based on the premiums they collect within the state.

Unemployment Insurance Taxes: These taxes are paid by employers to fund the state’s unemployment insurance programs.

Boat and Aircraft Registration Taxes: Some states require taxes for registering boats and aircraft.

Occupational Taxes: Certain states levy taxes on specific professions or industries.

That’s a lot of taxes.

How important are each of these to state and local government? While the exact numbers vary on a state by state basis, in the aggregate sales and use taxes account for around 35% of state revenues; income taxes account for about 25% of state revenues; excise taxes account for about 10%; property taxes about 5%; severance taxes about 5%; corporate income taxes about 5%; and other taxes and fees make up the rest.

Meanwhile, local governments are funded primarily by property taxes (40%), sales taxes (20%), income taxes (10%), excise taxes (10%), and intergovernmental transfers (20%) (e.g. the federal and state sends the local municipality money).

Net Rate of Taxation

With 30 different types of taxes operative across three levels of government, distributed across 50 states and countless counties and municipalities, the American system of taxation can only be described as Byzantine. The complexity is such that it can be quite difficult to calculate, exactly, what the net rate of taxation is on the average American — though we know it must be somewhere near 40%, less borrowing and inflation, because of the GDP measurements.

For taxpayers in the bottom quartile (lowest 25% of income), the federal income tax rate is between 0% and 5%. Payroll taxes are 7.65%, sales taxes are about 5% - 7% of income, property taxes (paid indirectly to the landlord) about 1% - 2%, and excise taxes about 1% - 2%. These households thus pay somewhere between 15% and 24% of their income to the government, either directly or indirectly.

For median (middle-income) taxpayers, the federal income tax rate is around 12% - 15%. Payroll taxes are another 7.65%. State income taxes are another 5% - 7%, sales taxes about 5%, property taxes about 2% - 3%, and excise taxes about 1% - 2%. The median taxpayer thus pays (directly and indirectly) between 33% and $40% of their income in taxes.

For taxpayers in the top quartile (top 25% of income), federal income tax accounts for 15% - 20% of income; payroll taxes 7.65%, dropping to 1.45% for wages over $160K; state income tax 5% - 7%; sales taxes about 3% - 5%; property taxes 2% - 3%; and excise taxes 1% - 2%. The top quartile taxpayer pays between 34% and 45% of their income in direct and indirect taxes.

For taxpayers in the top 1%, income tax (including the lower capital gains tax rate) is typically around 27% - 30%; payroll taxes are only about 2% - 3%; state income tax around 8% - 13%; sales taxes around 2% - 3%; property taxes around 2% - 3%; excise taxes around 1% - 2%. The top 1% might pay between 41% and 53% of their income in taxes, directly and indirectly.

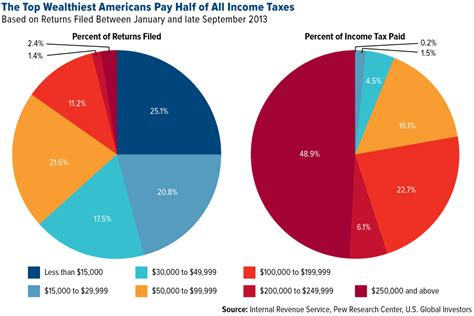

A common complaint among left-leaning pundits is that “wealthy households don’t pay their fair share of taxes.” It is true that high earners often manage to pay much less than the might otherwise due to sophisticated tax avoidance. But the only tax that can easily be “avoided” is the income tax; and even after taking tax avoidance into account, the wealthiest Americans pay half of all income taxes.

A common complaint among right-leaning pundits is that “working class households don’t pay taxes.” It is true that the U.S. income tax at federal and state level is highly progressive, being as low as 0% for low-income households, up to 40%+ for the top 1%.

When viewed more broadly, however, working-class households pay a lot of taxes. U.S. payroll taxes and sales taxes are highly regressive (7% and 7.65% respectively for the bottom quartile, down to 2% - 3% respectively for the high earners). Working-class households don’t pay as much taxes as high-income households, but as a percentage of their disposable income, their effective tax rate is about as high.

The Physiocratic Theory of Taxation

As a lapsed libertarian, I am of course arriving at this topic from my earlier libertarian viewpoint that taxes are an unmitigated evil and should be replaced with voluntary payments and/or abolished along with government altogether. On my way to becoming the Contemplator on the Tree of Woe, I sadly concluded that neither anarcho-capitalism nor Rand-inspired libertarianism had the answers I sought.

I remain of the conviction, however, that if taxation is to be moral and legitimate, then (a) it must be in service of a moral and legitimate government; (b) it must be imposed in a manner that is reasonably related to the government’s services; and (c) its cost should be born, not by “the poor” or “the rich,” but by those who benefit most from its services.

The first principle dictates the type of governments that can legitimately impose taxes; the second principle dictates what types of taxes those governments can rightfully use; and the third principle dictates who can be charged those taxes and how much they can be charged. The physiocratic theory is effectively neutral about whether a tax should be “progressive” “flat” or “regressive.”

If we follow the American tradition that men establish governments in order to secure their rights, then a moral and legitimate government must provide services related to securing rights. It seems to me that the services of such a government can be reduced (at a bare minimum) to four:

Maintaining peaceful transfer of power over time;

Protecting the person and property of citizens of the state from violation;

Securing the state’s borders from incursion and invasion; and

Upholding the legitimate contracts made by the state’s citizens.

Obviously a government surely can do other things, and most governments do many other things, but a government that cannot do what’s necessary to provide these four services will be a government that fails its necessary purpose.2

Working from this core of four services, I have identified four taxes that can be imposed in a manner that is reasonably related to those services and paid by those who benefit from them. These four taxes are:

Poll taxes

Land-value taxes

Customs duties

Transaction taxes3

Today, we’ll discuss poll taxes.

The Poll Tax

A poll tax is a flat charge imposed on each eligible individual (usually adult citizens), without taking into account their financial situation. Certain civic privileges, like registering to vote or obtaining state-issued licenses (such as driving or hunting), are often tied to paying this tax. In some regions, the poll tax is "cumulative," such that if someone failed to pay in previous years, they had to settle those past dues before accessing the restricted privileges again.

For our purposes, a poll tax can be cleanly linked to two of our four pillars: it can pay for maintaining peaceful transfer of power over time4 and it can pay for the protection of persons.

Maintaining Peaceful Transfers of Power

In 2020, the total cost of election administration nationwide was estimated at around $2 billion per year. This includes expenses like voting equipment, transportation, training poll workers, and maintaining secure voter registration systems.

There are 168 million registered voters in the United States. However, many registered voters fail to exercise the franchise. In the hotly-contested 2020 Presidential election, only 67% of registered voters went to the polls; in a typical midterm, only 40% - 50% of registered voters go to the polls. If a poll tax is charged to access the polls, the numbers will be lower. Let’s assume only 33% of the voters maintain their registration, e.g. 55 million. The poll tax would need to be ($2 billion / 55 million) = $36 annually.

Protection of Persons

In 2021, state and local governments spent approximately $135 billion on police, with local governments bearing the majority of this cost. Federal contributions were smaller, with the DOJ budget for law enforcement totaling around $40 billion for 2024. Fire department budgets vary widely across localities, as fire protection is typically handled at the municipal or county level, but is estimated at $25 billion. Combined annual spending on police and fire departments nationwide therefore equals around $200 billion.

Let us assume that protection of persons will be guaranteed to all residents. Therefore, all residents should pay this portion of the poll tax. With 330 million residents, the poll tax would need to be ($200 billion / 330 million) = $606 per person.

Net Rate of Taxation

What would be the net rate of taxation from the poll tax on American households?

Poll taxes are widely condemned by progressives and liberals because they tend to be highly regressive. But that does not necessarily mean they cannot or should not be implemented. After all, the current U.S. system has two highly regressive taxes (payroll and sales) as well as a number of taxes that are effectively regressive when spending habits are taken into account (property, excise, etc.)

The median household size in the U.S. is 2.5 persons per household. The poll tax would therefore be $1,515 for protection of persons and no more than $90 for voting, $1,605 total.

Bottom quartile taxpayers have a median household income of approximately $20,000 per year. The poll tax would be an effective 7.6% of their income, virtually identical to what they pay in payroll tax or sales tax currently.

Median taxpayers have a household income of $74,580 per year. The poll tax would be 2.1% of their income, equivalent to excise taxes.

Top quartile taxpayers have a household income of $150,000 per year, so the poll tax would be a mere 1.07% of their income.

Top 1% taxpayers have a household income of $540,000, so the poll tax would be an insignificant .29% of their income.

The poll tax is thus a low tax for all but the lowest-income households, for whom it is about as onerous as the current system of payroll taxes or sales taxes.

Next week, we’ll delve into another government service and look at how the physiocratic platform would tax it. For now, contemplate the poll tax on the tree of woe!

In this discussion, we will not be attempting to “cut spending.” Obviously, there is an enormous amount of bloat in our government, and we could and should cut that spending. However, a taxation scheme that starts by talking about spending cuts is usually doing so because it cannot actually replace the taxes it claims it can replace. Therefore, without being an advocate for Big Government, I am going to think about tax levels as if we are stuck with Big Government.

I will leave it to the reader to consider whether the U.S. government today is providing these services.

Also known as automated payment taxes, automated deposit taxes, universal exchange taxes, tiny taxes, and turnover taxes.

The 24th Amendment, ratified in 1964, abolished the use of the poll tax (or any other tax) as a pre-condition for voting in federal elections. Critics of the universal franchise believe this is a mistake, of course. Should it be necessary, repeal of the 24th Amendment could be part of the platform. That said, at just $36, it might be best to just add it in for everybody and address concerns about democracy in another way.

Poll taxes? A tough sell politically. But theoretically sound.

One want to make this more politic would be to have the federal government run a profit, and give out dividends -- but local governments get a poll tax's worth of that dividend. Use that as a replacement for all federal aid to localities, save perhaps disaster relief.

What about royalties on mineral extraction as a source of sovereign revenue?

That's lindy.